In our most Pirandellian chapter yet, Moscarda’s multiple selves have a crowded chat with however many Didas and Quantorzos happen to be in the room with them. It’s absurd and hilarious. It’s dark and utterly, utterly terrifying.

A horror of the whole of that body

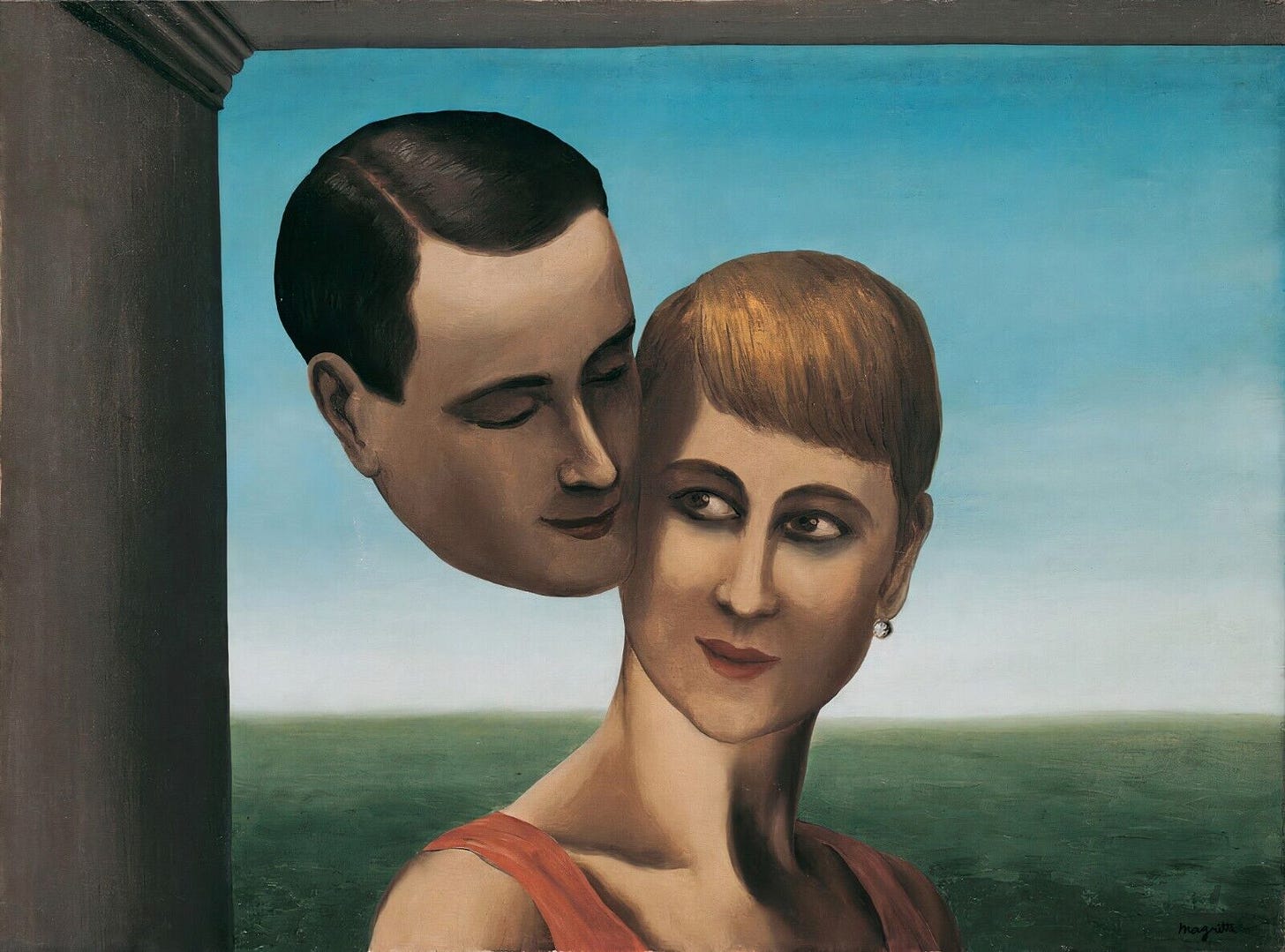

We were two strangers, two strangers—the horror of the thing—locked in an embrace, strangers not merely one to the other, but each to himself, in that body which the other clasped.

After the disastrous scene at the expenses of Marco di Dio and his wife, Moscarda flees public judgment and hides behind Dida’s skirts. To townspeople his actions were proof of insanity, to Dida it was merely a practical joke by her silly Gengé—in bad taste but ultimately harmless. Don’t we all wish for that, a partner taking our defenses, a safe haven against the cruelty of the world? Moscarda can no longer pretend that that’s the case: in his eyes, even the person who should understand him most has misunderstood him completely.

I don’t know about you, but my first instinct, just like Pirandello intended, is to laugh, shake my head or roll my eyes at Moscarda’s antics. My second instinct is wanting to reason with him or to offer practical solutions. Of course your wife is going to be her own person, I picture myself telling him, of course she will have different opinions! All that I’ve learned about relationships and healthy dialogue pops into my mind, and I cling to it because I still want to believe in human connections.

And here is where empathy kicks in, I forget my bias and walk for a minute in Moscarda’s shoes. Here’s where comedy becomes tragedy, and we let ourselves peek at the horror wreaking havoc in this poor man’s mind; I believe this chapter is the scariest yet, because we truly begin to see the consequences of extreme depersonalization.

You, I know, have never experienced this horror; for the reason that all you have done, ever, has been to clasp in your arms the whole of your world, in the person of the woman who is yours, without the faintest suspicion that she all the while has been embracing her world in you, which is another one, one where you may not enter.

What Moscarda is going through with Dida is no mere difference of opinion. Imagine losing your own sense of identity, your ability to communicate with others, your faith in the very mechanics of existence. Imagine being locked out from all relationships and experiencing inescapable loneliness. Imagine having all your beliefs replaced by uncertainty and emptiness. The existential horror of it all.

I refuse! I refuse!

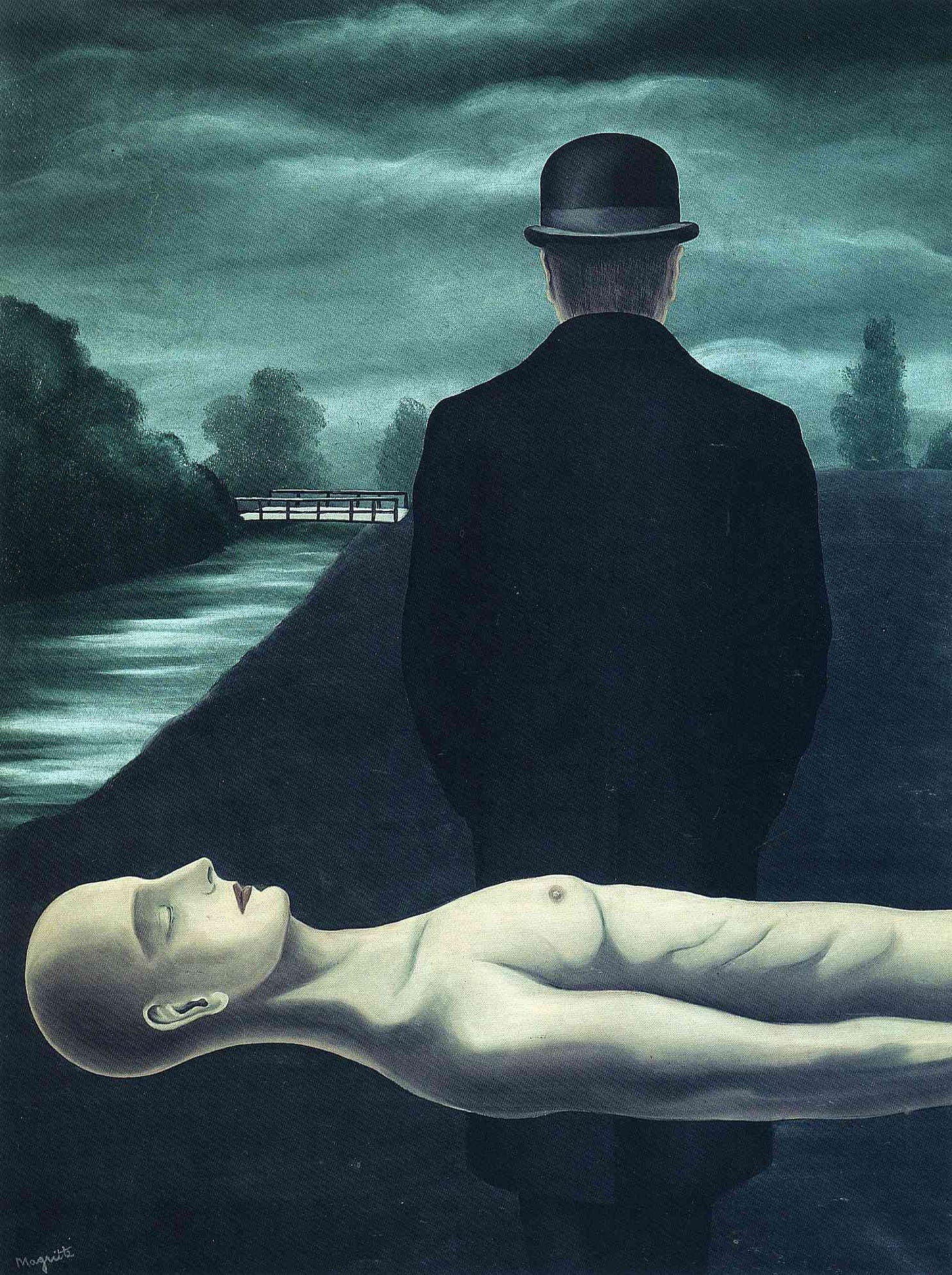

It was this; the horror of something which, from one moment to the next, might be revealed to me and me alone, beyond the range of others' vision.

Can we all spare a thought for Bibì, a wonderful puppy that didn’t deserve to be kicked?

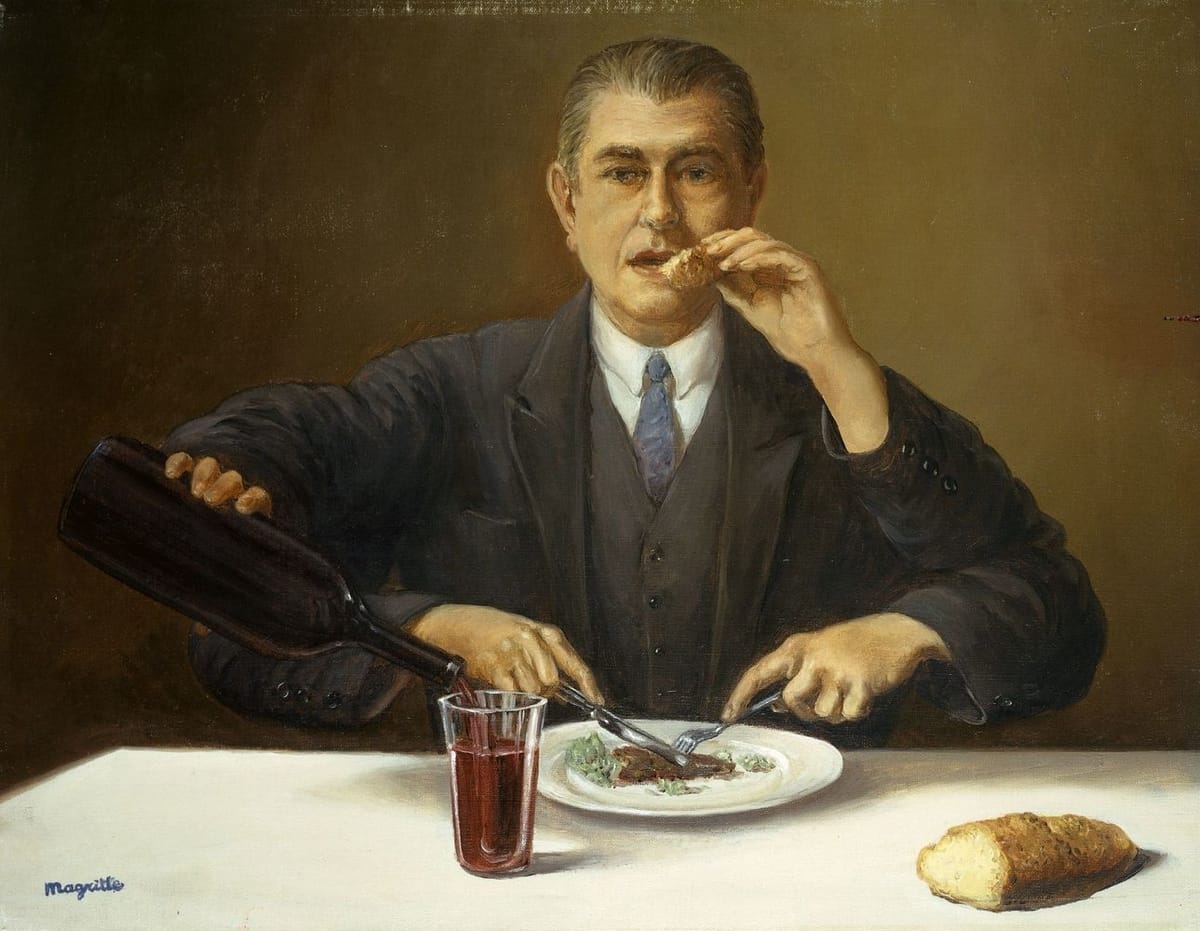

Moscarda squatting in a smelly corner, having a serious conversation with a little dog is a perfect storm of absurd, sweet and upsetting. Bibì sneezes as theatrically as the man in the mirror sneezed, both are soulless bodies giving in to physical urges (possibly, as dogs won’t confirm or deny any soul allegations). Moscarda is grappling with flesh that he no longer feels his own, a body that he pilots around for other people’s consumption, totally alienated from his inner self. When it all becomes too much, instincts take over and the dog gets kicked. Notice what happens next: Moscarda gains yet another alter ego, the monster who kicks innocent creatures, who’s also a boy lost in the countryside and scared of the unknown. So many split personalities forming a single, very troubled person.

No, no! Not I! A certain overgrown, shamefaced country lad might have done so, on account of some strange fear or other that had laid hold of him, a fear of everything and nothing, a nothing that might in an unlooked-for manner become something which he then would be the only one to behold. But here in the city, now, here in the street, there was no longer any danger of that.

Moscarda inevitably fantasizes about suicide and how the people closest to him would react to his death. He puzzles on why we are driven to think of our own death from an external point of view—it’s for the same reason why as a boy he experienced profound horror when he got lost in the woods, because he had no one to share his loneliness with. We’ve talked about Nature as the only true happiness a person can experience, the only escape from the cage that is a fake, man-made existence. Here’s the other side of the coin: that very nature we all strive for is horrifying. Existing outside of human conventions is harrowing, loneliness is harrowing. That is why we can’t think of our death—it’s something that we will have to do alone, no one is going to share it with us. Nature is cruel and unforgiving, and we belong to it, no matter how much we try to pretend otherwise. In the end we are just bodies with delusions of grandeur, playing pretend, huddling together for comfort, waiting for the inevitable.

I know I’m repeating myself, but it really is enough to go insane. And doesn’t Moscarda’s insanity, so absurd and unrelatable at first, just grow more and more familiar? Couldn’t you see yourself going down that same route, if you only allowed yourself to think, to really think about the meaning of life?

"A delightful game! And who knows, my dear sir, my dear madam, what charming surprises you would encounter, if after having thus flung yourselves down from every illusion that you possess concerning yourselves, you could come back for a fraction of a second from the dead, to view in the illusion of others yet living that world in which you imagined that you lived! Ah, ha!" The unfortunate part was that, still alive, I had to witness this game among the other living, although I was unable to fathom it. And this impossibility of fathoming it, while all the time knowing that it was there, where everybody could see it, exasperated my mood of maniacal mirth to the point of savage fury. That kick which I had let fly at that poor little beast, simply because she had looked at me, I now felt, God forgive me, like bestowing upon all mankind.

The eight who believed themselves three

And no one stops to think that this is the way in which we all ought always to stare, each with eyes horror-filled at his own inescapable solitude.

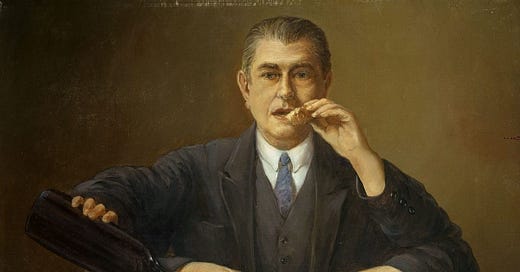

Moscarda comes back home to find Dida chatting with bank manager Quantorzo about his recent forays into madness. He does some quick math and concludes that there are around eight people in the living room: Dida herself, Moscarda's idea of Dida, Quantorzo's idea of Dida. Quantorzo himself, Moscarda's idea of Quantorzo, Dida's idea of Quantorzo. And finally Gengè (Dida's idea of Moscarda) and dear Vitangelo (Quantorzo's idea of Moscarda). There isn’t a ninth person because Moscarda has lost all sense of identity, he no longer counts as an individual, he's no one.

He's one, no one and a hundred thousand.

The conversation that follows between the three that are actually eight is a whimsical comedy of errors straight out of Pirandello's playbook. Dida dotes on her ridiculous Gengè, Quantorzo fails to reason with dear Vitangelo, and Moscarda grows frantic as he tries to distance himself from his father's shady business, until he commits the fatal mistake of putting everyone's money in jeopardy, we simply cannot have that! The joke is that humans are greedy! (Just don't think about these three poor people, each of them a whole separate world, stuck in a vacuum and talking to two shadows. Utterly alone. It's a funny scene if you don't think about that, I promise.)

That's enough of your Gengè! He's not I! He's not I! He's not I! Let's hear no more about that marionette! I want what I want; and what I want shall be done!

There is something so real and raw about Dida's growing horror as her husband destroys his identity and their life together. Going against the status quo will only bring chaos, even if Moscarda wanting rid of his unsavory reputation is pretty mundane and understandable. Trying to destroy the identity that society has assigned him is as futile as trying to be understood by a hundred thousand different people. He cannot escape the way others perceive him, he will only ever be Dear Vitangelo to Quantorzo, Gengè to Dida, the usurer Moscarda to people in town. His father named him like he named the bank, the parallel obvious and upsetting: other people perceive him like they would perceive a commodity. And if others are unable to accept our complexities, doesn't that mean each interaction will inevitably become a dehumanizing experience?

I want to take a second to thank each of you for leaving comments (I know I’m late in responding, I promise I’ll get to everyone), and also to those who read in silence, I see and appreciate you too. As you know, I’m having a really tough time lately, life has been giving me some real lemons in 2025, I used to be able to write a lot but even putting out one entry a week has become a struggle. Ha, you can probably tell, my own depression shines through my literary takes! But I’m proud of what I’m accomplishing in these less than ideal circumstances, and Pirandello’s hopelesness nonwithstaning, I know some human connection is possible, because we still get to reflect and discuss together.

Next week is a shorter one!

Ellie, I am sorry you are struggling through this year. Wishing you easier times. I am so pleased when I see your weekly essay appear. It is always intelligent and well written, unlike many other emails I receive. The sentences in this book have so many commas!!! I lose track of what is being expressed. Thank you for making sense of what I cannot make sense of.

I’m so sorry to hear that you’re having a rough time. If it helps at all, please know that your thoughtfulness, intelligence and generosity of spirit are appreciated by this random stranger on the internet. I hope things turn around for you soon.