On week one we made the acquaintance of our narrator, Moscarda the fly. On week two we met another version of him, silly husband Gengè. Today we discover a third identity: the son of the local loan shark. Will these three Moscardas be able to cohabit peacefully?

Well, you already know the answer.

What’s in a name?

My name, take it: ugly to the point of cruelty. Moscarda. Mosca, the housefly, and the shrill, annoying taunt of its tiresome buzz. The spirit that was I possessed no name whatsoever of its own; it possessed a whole world of its own that lay within; and I did not at every turn stamp with this, my name, to which in truth I gave no thought, all the things that I beheld within me and about me. All very good; but for others, I was not that nameless world which I carried around inside me, quite whole, undivided and yet varied.

When did your parents choose your name? Maybe you were just a few hours old, or maybe you were still inside your mother’s belly. Does a name that used to fit a screaming infant express everything you are today? And what about your last name? If you think about it, that’s merely a sound that you (in most cases) inherited from your father.

Like all of us, Moscarda is used to his name—people have been calling him by it since he was born. And like all of us, Moscarda sometimes experiences semantic satiation, a psychological phenomenon that happens when we repeat a word so many times it suddenly loses its meaning. Try it with me: pipe. Pipe pipe. Pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe. Pipe pipe? Pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe. Pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe pipe! Pipe pipe. Wait, what does pipe even mean? Pipe-pipe-pipe. What a strange sound. So silly to associate it to an image. And what about Moscarda? Moscarda Moscarda Moscarda Moscarda Moscarda Moscarda Moscarda. Try it with your name too. It’s like tricking your brain into dissociating noun from idea, sound from meaning.

So much of our existence is based on socially accepted constructs: the words we use to describe things, the value of money, a country’s borders, the list goes on and on. Sometimes phenomena like semantic satiation make the artificial nature of these constructs more obvious, but it only lasts a second: we’re too busy living our lives, and soon enough we’re swept away to attend more pressing matters.

Not Moscarda, though. The little epiphany about his crooked nose is turning into a landslide of new ideas; he can no longer forget what he discovered and go back to ‘normal’.

Conditioning circumstances

Whereas, it was not I who had fashioned that body, who had given myself that name; I had been brought into life by others without my will; and similarly, through no will of my own, so many things—above, within and round about—had come to me from others; so many things had been done for me, given to me by others, things of which, as a matter of fact, I had never thought, of which I had formed no image like that weird, inimical one with which they came trooping over me now.

Moscarda's reflection in the mirror was a stranger that had nothing to do with his inner life. His name is similarly dissociated from his sense of identity: when people think of him, they'll think of a short man with red hair and a funny insect-like name. There is nothing he can do to separate himself from these external factors that are irrelevant to him and character-forming to others—he will never decide, for example, to one day become a tall, handsome Scandinavian and have his wish granted.

In a much ridiculed interview actor Dustin Hoffman talks about the epiphany he experienced while starring in drag in the 1982 movie Tootsie. He had hoped to transform into a beautiful woman, and when he was told that there's only so much make-up can do, the realization was shocking.

“I think I am an interesting woman when I look at myself on screen. And I know that if I met myself at a party, I would never talk to that character, because she doesn’t fulfill physically the demands that we’re brought up to think women have to have in order for us to ask them out.”

Hoffman had probably met many women looking like Tootsie and never bothered to get to know the smart, funny person hiding behind those appearances, it took becoming Tootsie to feel empathy for them. In other words, he discovered that the opinion others have of you can be heavily influenced by external factors like physical appearances and social roles and expectations.

Girls in the comments, don't be too harsh on Dustin here, remember that social privilege is often invisible to those who wield it. I bring you this example because, well, it takes a VERY privileged and clueless individual to achieve an epiphany both so monumental and so obvious. Someone, for example, who never worked a day in his life or bothered to learn where daddy's money came from.

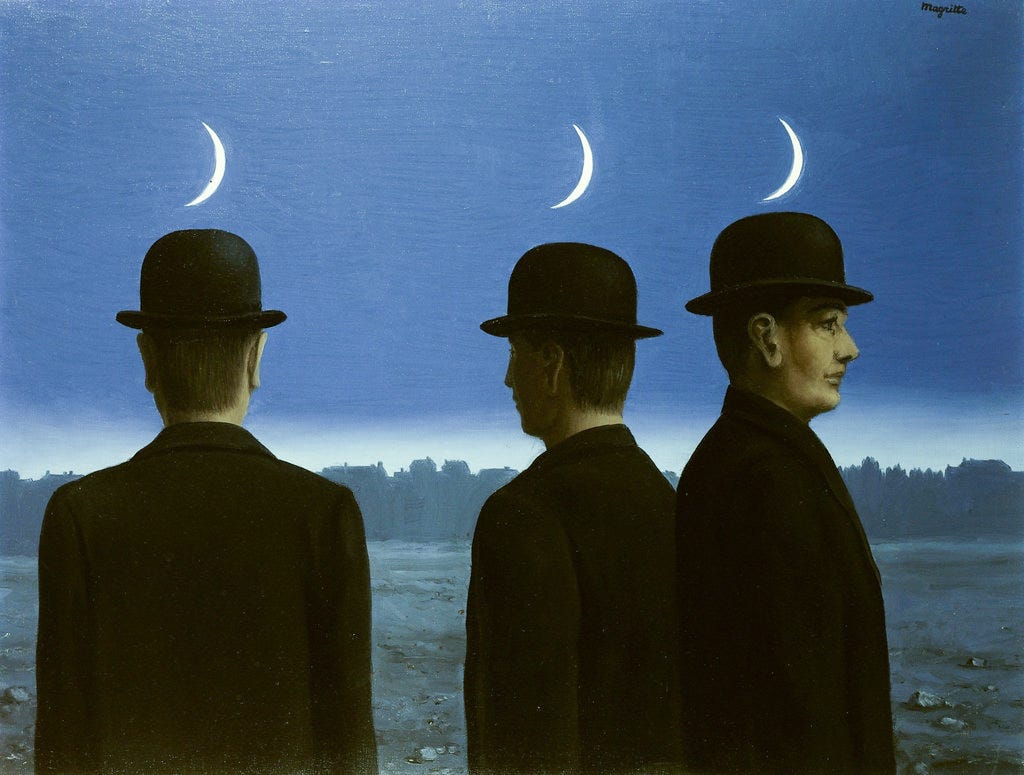

I've talked about Pirandello deliberately using humor and satire to illustrate his themes, and it's no coincidence that Moscarda is almost a caricature of a real person: when a clown discovers the world's folly, the comedy inevitably becomes grotesque and profound, like a Magritte's painting. Moscarda so far has cruised through life without a care in the world, oblivious to his own place in society. Who better to experience extreme drama when the figures in Plato's cave are revealed to be a scam?

Roots

I saw then my father for the first time, as I had never seen him before, externalized in his own life, but not as he had been to himself, not as he had felt himself to be, which was something I could never know; but rather, as a being that was wholly strange to me, in that reality which, as I now beheld him, I might suppose that others had imposed upon him.

When was the first time you realized your parents were not perfect? I was around nine or ten when I had a little epiphany of my own. I used to listen to my dad rant about this or that politician, puzzled at how such important people could take such evil decisions. Until one day I understood that no, other people are not evil on purpose, everyone thinks they're right in their own mind, and my father wasn't the sole custodian of truth. Feeling very smart, I announced, "Dad, you're not always right!" I hoped for praise, got slapped around the face instead. True story.

Pirandello too was just a kid when he had his realization. He'd learned that his father was seeing another woman behind his mother's back and, enraged, had surprised the two lovers canoodling in a private room inside a convent. What followed was a fight so humiliating that Pirandello Sr. went straight home to beat up his poor wife out of spite. Sounds like a capital fellow!

In comparison, our Moscarda made it all the way into adulthood too busy daydreaming to ask himself a few choice questions about his family. Only now, when his sense of identity has been linked to his father's genetics and life choices, the realization hits him like a ton of bricks, and it's charming in all its dramatic absurdity. As it turns out, if you are the son of the town’s most infamous loan shark people might be a tad prejudiced about you. And if you prance around idly babbling about clouds and noses, people might even think you’re a jerk or an idiot.

How does it come that they had not knocked me in the head and had done with it long ago?

(Reader, I laughed.)

Moscarda has just discovered what we all more or less know but, as usual, choose not to delve in too deeply for our own sanity. We like to think that we came into this world like blank slates, with endless possibilities and opportunities ahead of us. The truth is, we are just the last link in a long chain of human baggage, already doomed by our own genetic markings, our place in an arbitrary constructed society and the decisions our ancestors made. We are fools seeking free will from behind the bars of our own cages.

And how can anyone live like that?

Mistakes or crimes

says that she’s been struggling to see Moscarda as completely separated from Gengè, and that is a good sign in my opinion. It means that you’re not going insane yet. It’s impossible to not recognize in him Gengè’s clueless nature (he just asked Dida what was his father’s profession!) He is also the very same idiot that people in town have been calling Moscarda the usurer. His three identities are one person, easily identifiable by date of birth, name and address, and that is a fact.Time, space: necessities. Fate, luck: accidents. Life's traps, all of them. You will to be. There is that. But in the abstract, there is no such thing. Being must be snared in form, and for a time come to an end in it, here or there, in this way or that. Everything, so long as it endures, bears with it the penalty of its own form, the pain of being the way it is and of not being able any longer to be something other.

says that symbols are not the same as the reality that they represent and humans will inevitably get in trouble blurring the difference between the two, even though creating symbols is a fundamental part of human nature. I’ve been calling them social constructs or conventions instead, but you get the gist.“What about facts?” you exclaim. “Good heavens, is there no such thing as facts, the data of facts?”

We need facts, to function as a society. And we also need to understand that facts are not really true, they are conventions, approximations of realities that we are too limited to express or comprehend fully. How do we make it make sense?

Example: five people look at Moscarda’s house and they agree on the facts, address, color, height, number of rooms. But you just have to ask, and one will tell you the house is fancy, one will call it vulgar, one will associate it with a sad or a happy memory and so on and so forth. Differences of opinion, you might say, inconsequential. But what happens when you ask twelve jurors to decide whether someone is guilty or not? How can you possibly call that justice if changing the jurors might give you a different outcome? The answers is, you have to, because that is the best approximation of a fair trial we could come up with.

Actions must be judged and punished accordingly, that is a fact, but I promise that the more you dig, the more nuance, layers and moral conundrums you’ll find. When does a mistake become a crime? Who deserves our empathy? Ask ten people and you will receive ten answers. To judge someone in any setting is to oversimplify them. We label and imprison a complex soul into a neat cage and call it a day. We make the infinite finite. We have to, because the alternative is having a criminal running free in the streets.

And life knows no conclusion. It cannot know any. If tomorrow there were to be a conclusion, all would be over.

Moscarda can no longer accept the conventions of civilization. He calls them for what they are, lies, abominations, the antithesis of life. But since he can’t find an alternative to living in a society (no human can) what’s left for him to do? He can only go insane.

What is madness, anyway? Many smart people have written that it’s the only sane option. I personally don’t agree, but maybe you do.

As we are about to meet even more characters, would you like a list or guide to keep track of everyone? How are Italian names treating you, are they very confusing? Let me know, and see you next week!

Moscarda perhaps should read Walt Whitman, “ I contain multitudes.”

Another interesting week of reading - and fascinating insights from Ellie. I was struck with the idea that each observer creates a unique version of the observed. That each person takes the same set of facts and creates their own truth from it. I’ve often mulled on the idea that everyone who reads a novel has their own unique vision of it - what the characters look like, how they dress, what their homes and landscapes look like. This is true even when the author has described those things in detail. Imagine how many million Elizabeth Bennetts there are or have been. How many Holden Caulfields. And how cross we can be when we see another person’s version brought to life on screen! This line of thought got me noodling on the idea of the universe contained within each one of us. A unique, never-to-be-repeated place that’s completely inaccessible to anyone else. For a terrific pop-culture meditation on this I recommend Stephen King’s horror-free Life of Chuck.

I’m doing ok with the Italian names! Personally I don’t need a character list (that sounds like a lot more work for you 😆).

I’m looking forward to reading everyone’s thoughts on this week.