Welcome to Week 2 of our read along! This entry covers pages 7 to 18 of the Vintage Classics paperback edition, starting from “Those audiences! All those audiences granted him by King Ferdinand,” and ending with “Towards dawn, however, the Princess had occasion to make the sign of the Cross.”

But before we dive in, let’s zoom all the way out and take a quick look at Europe as a whole. I’m trying to keep history lectures at a minimum, but if something isn’t clear do ask me!

A long, bloody century

19th century Europe was on fire, and I don’t mean it figuratively. The first Industrial Revolution had just happened, capitalism was a new and exciting concept, business owners suddenly had a lot of wealth and political power; poor workers, now crammed in city factories, had grown a political stance of their own, thanks to the ideas of one Karl Marx. These two groups, bourgeoisie and proletariat, hated each others’ guts, and hated the upper classes even more. The inevitable result was that Paris kept burning: the French could never say no to a good old popular insurrection.

Except, it wasn’t just France. Berlin was also burning, and Prague, Vienna, Budapest and many, many others. What about Italy? Yup, you guessed it.

Italy was a blood bath. People were fed up with foreign rulers and demanded an united, independent state. What that would look like was a whole other can of worms. (Constitutional monarchy? Strong central republic? A cool federalist republic, like the Americans? Do we just put the Pope in charge and call it a day?) But that was a problem for later. Now it was time to fight, and fight they did, in an endless series of riots and revolutions and full on Independence Wars called Risorgimento (the Resurgence), which is the stuff of nightmares for any poor Italian student. Austria kicked our butts repeatedly with General Radetzky and then wrote a march about it. Very funny, Austria.

As for Sicily—oh boy.

Sicilians, as you can imagine, were thrilled to have yet another oppressive regime ruling from afar, stealing their resources. 70,000 people had just died of cholera, and the government simply didn’t care. Sicilians had caught the revolutionary bug like everybody else, and in 1848 they actually went and declared independence. Guess how that went.

King Ferdinand II had (one would imagine) a good laugh about it and sent his army over. His nickname was Re Bomba, because he had a knack for bombing away his problems. He was an old-fashioned king, none of that constitutional rights nonsense: if his subjects disobeyed, his subjects died.

Sounds charming, doesn’t he?

King Bomba

Fellow readers of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy will recognize what Fabrizio is doing in Ferdinand’s presence: he arranges his face, wears the mask of a faithful courtier, pleased to serve his master. It’s an unsavory business, our mighty Jupiter having to bow to a bigger fish for once. Fabrizio’s judging eyes linger over the shabby décor tainting the Royal Palace of Caserta, the cheap religious prints sitting next to a priceless, bewildered Madonna. (Have you noticed how inanimate objects seem to spring to life around our prince?)

The contrast between tacky and elegant conveys the image of a goofy, down-to-earth King. Except, we’re quickly reminded that his study is consciously simple. He leaves his guest standing for a moment too long, asserting dominance. His mouth laughs jovially while his hands move angrily. He’s wearing a mask too.

After this, however, the mask of the Friend was put aside, and in its place assumed that of a Severe Sovereign.

We get only a glimpse, a calculated, deliberate glimpse of the reactionary bombing king, with his denial of science, the chilling menace behind good-natured vulgarity. Others might see Ferdinand as someone nobler than a mere bully; Fabrizio, smarter than the average person (or so he tells himself) is left disgusted by the hypocrisy of it, the humiliation of it. Still, he goes through with the pantomime. Like a leopard defanged, he wears his fake smile and laughs at fake jokes.

Even if the wind is changing, even if the Bourbons will inevitably bow down to a new foreign king, the Prince of Salina will still find himself at court, his conscience aching and his title safe and cushy. Who’s the hypocrite now?

Necessary sacrifices

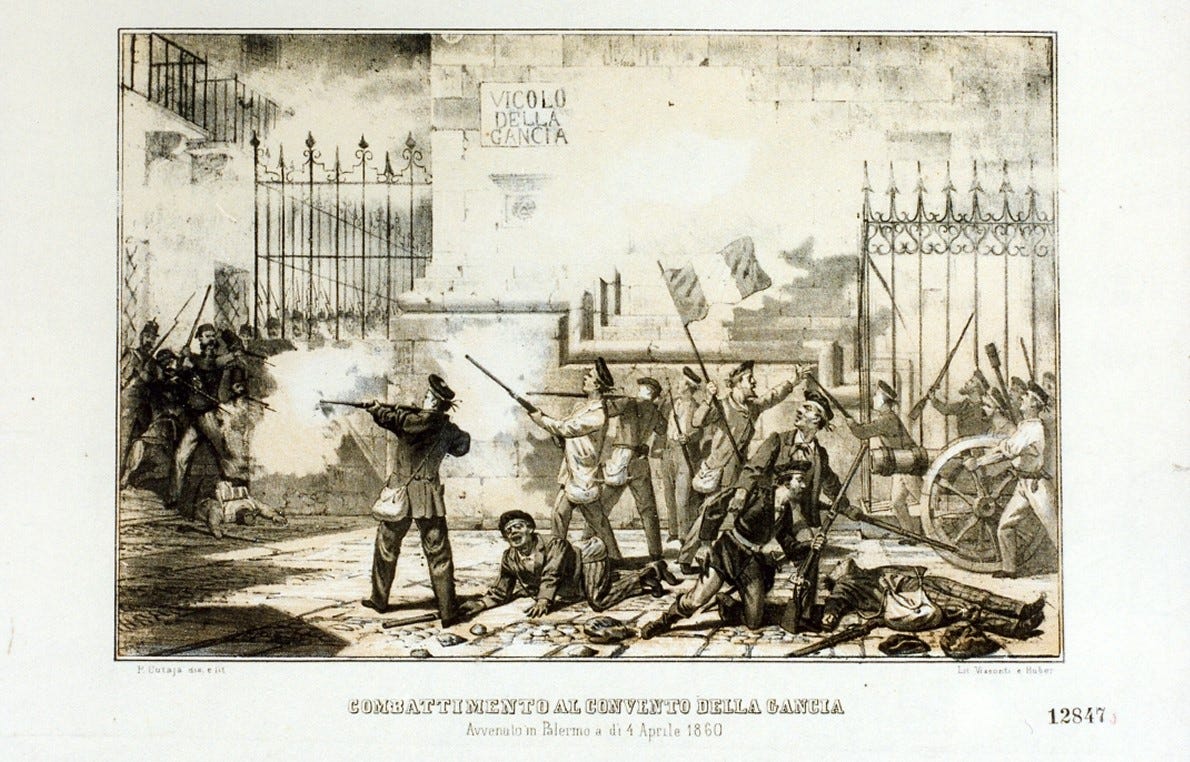

During the night between April 3rd and 4th 1860 a group of conspirators sneaked into La Gancia, one of Palermo’s many monasteries, where they had previously hidden some weapons. They were Freemasons, atheists, anti-monarchists, extremists of the worst kind (at least according to old families like the Salinas).

Their plan was simple: wait until daybreak and start an uprising. They didn’t know that a friar had betrayed them: at five in the morning, the sky still dark, police stormed the monastery. Most rebels were killed on the spot, with only a few captured alive.

News spread fast, fights broke out all over the city and on the hills and villages surrounding it. (In our book, the Salina girls were hastily withdrawn from their boarding school, and a soldier dragged himself to die inside the Prince’s garden.) To set an example amidst the disorders a public execution was ordered for the prisoners. Thirteen men faced the firing squad, with a crowd screaming in the distance, and were then tossed into a mass grave. The oldest was 63, the youngest 15.

A month later, Fabrizio is still haunted by the sound of those rifles, the smell of that corpse. Borbonic soldiers or Sicilian rebels, they all died like unaware extras in that same play he performed with King Ferdinand. He didn’t want to rock the boat, he didn’t speak up. As always, he’s frozen in the middle.

“One never achieves anything by going bang! bang! Does one Bendicò?

“Ding! Ding! Ding!” rang the bell for dinner.

It’s still the same evening, we’re still in the garden. Fabrizio’s memories have wandered, flashbacks nestling like Russian dolls. With a rather cinematic trick the sound of shots is replaced by the dinner bell, blood is replaced by food, the cycle continues.

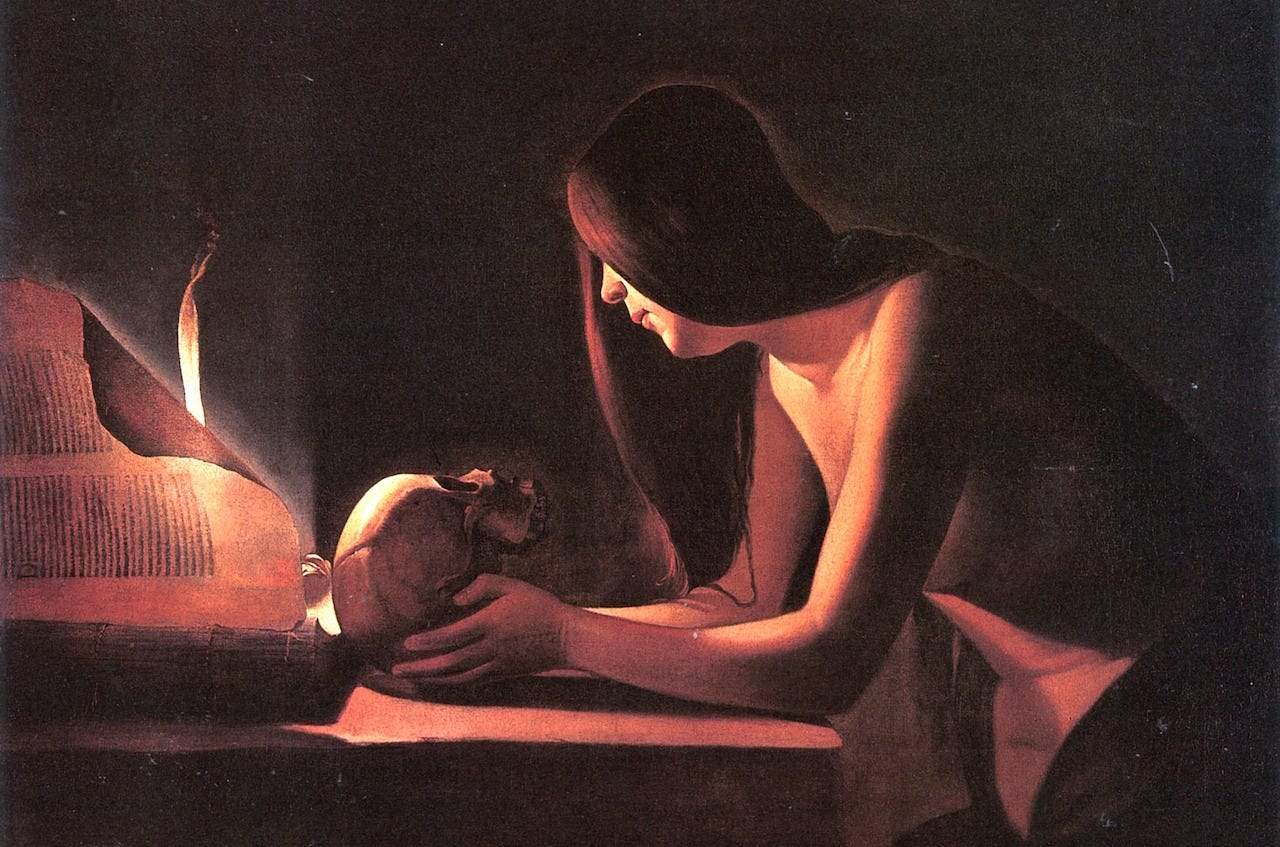

Chiaroscuro

Jupiter is once again king of his dominions. The dining room is bathed in shadows, despite the sun shining outside; the beautiful table cloth is mended, the fancy plates are mismatched, the grand house of Salina is just as tacky, just as rotting as the house of Bourbon. And isn’t Fabrizio a small-town Ferdinand after all? Isn’t he wearing the mask of almighty pater familias, hiding the turmoil underneath? Aren’t his subjects trembling in the shadows, waiting for the bomb to explode?

(Forty years later, a son recalls the terror of those moments. Little Giuseppe Tomasi listens attentively: our author waves from his writing desk, reminding us that he’s part of the story too.)

Fabrizio’s anger is performative, just like the King’s. His family is kept at a distance, bullied and scared; his love and his pain are private. He lingers on another harrowing memory, his son Giovanni, the second eldest, the most beloved, the most difficult. Out of his seven children, Giovanni sounds like the most similar to the Prince: he too could see how meaningless, how maddening Sicilian life is. But unlike Fabrizio, he did something about it: he left. The pain for a missing child now mixes with shame, with envy.

The hills are alive

With the overpowering urge to exorcise his feelings, Fabrizio heads downtown for a romantic encounter, chaperoned by a long-suffering Father Pirrone. The dark hills are flickering with fires, the unrest that followed April 4th still hasn’t died down; it’s not going away, the old regime is starting to realize. (Fabrizio suspects that his new favorite child, nephew Tancredi, is sharing a bonfire with the rebels. He’s like Giovanni, unafraid to rock the boat. Despite his staunch Borbonic persona, Fabrizio can’t help admiring and even aiding him.)

As practical Pirrone reflects on the political implications, the Prince’s moody inner life absorbs and transforms his surroundings, just like with the paintings, just like with the garden. Funereal, empty Palermo grows alive and tangled, its many churches and monasteries towering over it; the city mirrors the garden, but upside down, like Dante’s inferno. Dead giants now sit on the surface, oppressive beasts looming in the dark, stealing the life underneath. Fabrizio is up there, reaping the benefits of the ruling class, and he’s also at the bottom, his life sucked dry.

Bishops and abbots, kings and princes, beasts who have ruled for centuries and centuries, are men like those on the hills that will soon replace them. They don’t even want power, Fabrizio muses bitterly. Deep down, the beast that is called man can desire only one thing: oblivion.

Small deaths

Oblivion is what Fabrizio is really after as he stalks the desolate streets of Palermo, where soldiers patrol and civilians cower. He wants to stop hurting, to stop desiring, fearing; he wants to stop thinking. His two natures, the pagan hedonist and the devote aristocrat, are in perpetual, exhausting fight. Everything he does, one way or the other, brings guilt: bowing to Ferdinand, abusing Stella and Pirrone, helping the revolution through Tancredi. His Christian upbringing, always seeking atonement, clashes with heretic desires. He resents and envies his twin of a son, living among heathens in London.

“I’m sinning, it’s true, but I’m sinning so as not to sin worse, to stop this sensual nagging, to tear this thorn out of my flesh and avoid worse trouble. That the Lord knows.”

Can there be something more paradoxical? He’s sinning in order not to sin. If he can stops himself from yearning, then everything will be fixed. If he can lose track of time behind his telescope for one evening; if he can forget himself within a good orgasm—after all, there’s a reason the French call it la petite mort. It never lasts. He comes back to the land of the living a sinner, and he feels sorry for the prostitute he himself is dehumanizing, he feels sorry for the men his own apathy has sent to death, he feels sorry for his belittled wife. Most of all, he feels sorry for himself. But not enough to change his ways, apparently.

Baudelaire wrote: “Lord grant me the strength and the courage to contemplate my heart and my body without disgust.” A long-forgotten poet, thinks Fabrizio, whose perception of the world is as always accurate and misguided. Baudelaire, just like Giuseppe Tomasi of Lampedusa, found fame only after death.

asked an excellent question last week: what is Fabrizio’s true religion? He prays Christian prayers but seeks ecstasy and sublimation like the ancient gods on his walls. We’ll explore this duality much further, so keep an eye out for it.Men and beasts

Bendicò uproots life in the garden with gusto, he disregards Fabrizio’s musings on mortality to get to his dinner faster, just like a person would. Mariannina submits unthinkingly to Fabrizio like Bendicò does. Father Pirrone is a shepherd dog obeying orders from above. Even the rotting boats of Palermo look like mangy dogs. Are men like dogs or are dogs like men?

A symphony of contradictions

I’m not pointing out every oxymoron we’re coming across because, well, it would be endless. But do look for them, notice each time you read descriptions such as shabby grandeur, cold and respectful, weak heavy steps. The author is hiding his leitmotif within each note, meticulously and deliberately, and if you step back, you can already listen to the forming symphony. Keep this in mind next week as we finish the first chapter.

Here is the reading schedule, and don’t forget to check the character list if you can’t remember who’s who. If you haven’t already, consider subscribing to receive new entries via email.

How do you feel about our story so far? Are you enjoying it? Is the existential dread setting in yet? What do you think is going to happen next?

Till next time!

You said you would try to keep the history lectures to a minimum, but I enjoy them! - it enhances the reading experience for those of us without much knowledge of 19th century Italy. With gratitude!

I’m enjoying both the book and your interesting notes. As a fellow Wolf Crawl slow reader I thought that in this week’s section the Prince reminded me a bit of Mantel’s H VIII - both self flagellating and self pitying. Everything is always someone else’s fault - especially those old, religious wives!