At long last here we are, about to listen to Moscarda’s version of events one last time. You might believe him or you might not, it no longer matters. We are finally at the end of our story and about to reach a resolution to our little alter ego problem.

Any minute now.

The overflowing river

Nevertheless, they all insisted upon calling me Moscarda still, although the name Moscarda surely held for everyone a different signification than before; and it seems to me they might have spared that poor nobody of a pauper, as he stood there smilingly in his wooden sandals and his sky-blue blouse, the pain of having to turn around once again at the sound of that name, as if it really belonged to him.

What happened to Moscarda after the embarrassing predicament of bleeding out on the bed of decidedly not his wife? Well, by his own admission, he went and lied to the authorities about it.

It was a dutiful lie, he explains earnestly, meant to save Anna Rosa from prison. As expected, nobody in town believes him—after all, who “accidentally” keeps a loaded gun under her pillow? It’s even more absurd than swinging it around in your purse! Dida is all too happy to report her adultery suspicions, and the judge assigned to the case is determined to dig deeper. Meanwhile, Moscarda has dismantled the bank and, urged by Father Sclepis, used up all the money to build a poorhouse and soup kitchen. Alone and stripped of all his earthly possessions, his new and unusual circumstance (plus Anna Rosa’s confession) eventually clear his name. Not that he wants anything to do with his name anymore.

Moscarda’s transformation from local usurer to local madman is complete, yet people are still using the same old, fly-like name to gossip and laugh at him: not even annihilating his whole sense of identity was enough to escape it. People will always mock or scoff or get angry rather than try to understand. It makes us feel less scared, more justified in our own choices. And so the courthouse laughs at his new pauper attire, and Sclepis grows incensed at the alleged adultery—Moscarda idly notices how the priest’s fire-and-brimstone speech stems less from a genuine desire of helping and more from personal pride. He is annoyed at being once again misunderstood, but no longer has it in him to protest. Like a siren call, spring is beckoning him outside.

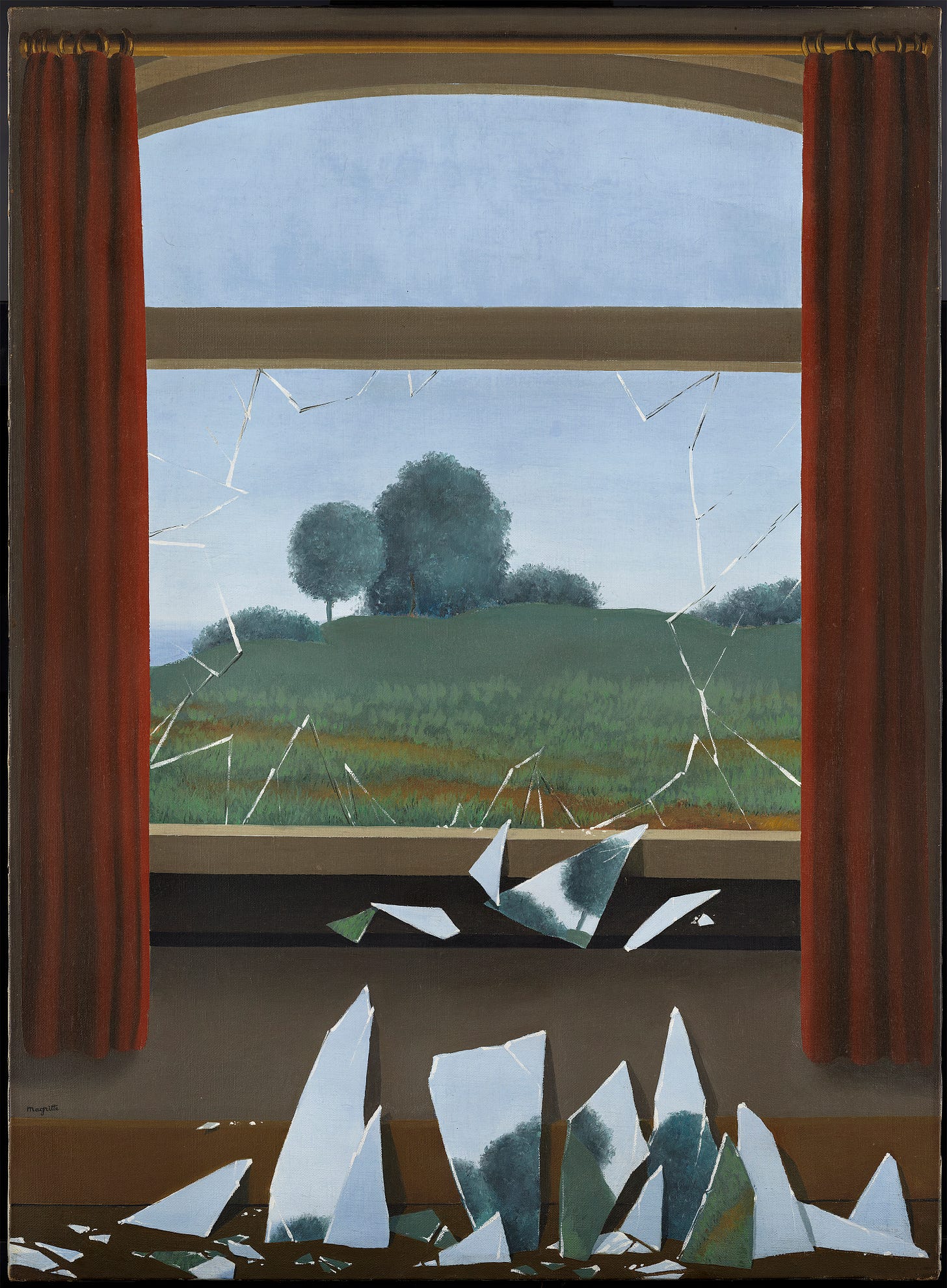

I had a glimpse of the countryside, seemingly one boundless expanse of grain; and fondling it with my eyes, I reveled in it all, really feeling as if I were in the midst of all that grain, with a sense of timeless distance that filled me with the gentlest sort of anguish.

When the judge visits him, a recovering Moscarda is distracted listening to the sounds and smelling the scents of nature coming from his window. A strange and alarming yearning as taken over him, but for now he can only fixate on his artificial blanket, the closest thing to a green meadow he can find in the house-cage. Not even the presence of the judge—the most criminal and unnatural of professions in Moscarda’s opinion—has the power to anger him anymore. He is sweet and forgiving as he explains that our secure life, our organized rules of civilization, are just a series of artificial dams and river banks that temporarily contain but can never, ever stop the whirlpools and currents running underneath.

Now the river has overflown like it was always going to, and the person once known as Vitangelo Moscarda can only swim in the chaos of it.

Rebirth

Behold him, then: for himself, no one.

Could it be that this was the path that led to becoming one for all?

It’s no coincidence that the poorhouse is sitting in the countryside, surrounded by nature, in the freedom that Moscarda the caged canary has been yearning all along. The description of his morning walk never fails to bring me to tears, the simple beauty of it turning sublime under Pirandello’s expert pen.

And the air is fresh. And all, from second to second, is as it is, revived to take on appearance. I quickly turn my eyes in order not to see again anything coming to an apparitional halt and dying. So only can I go on living, henceforward. By being reborn second by second. By seeing to it that thought does not once more start working in me, and within me refashion the void that goes with the vanity of building things. The city is far away.

The total rejection of civilization, of its rules and conventions. No philosophy, no sense of identity, just a body feeling the warmth of spring. Is such a life even possible? Could a human being regress to this atavistic state, forget millennia of evolution, be content living as a newborn animal, entirely pure in its clueless innocence?

The ending is a prayer that Pirandello sends out to the universe, and it’s as beautiful as it is useless. We all seek enlightenment, we fantasize about bypassing our fears, our loneliness, our need to understand, our mortality no longer torturing us. All names, all identities will find their inescapable end on a gravestone, but as long as he has no name, as long as he is reborn moment by moment like a fawn in the forest, he no longer fears death. That is why he won’t end his story.

Refusing to engage, escaping other people, fleeing mortality: is it enlightenment, or is it cowardice? I guess it’s up to each of us to decide.

No name. No memory today of yesterday's name; of today's name tomorrow. If the name is the thing, if a name in us is the concept of everything that is situated without us, if without a name there is no concept, and the thing remains blindly indistinct and undefined within us, very well, then, let men take that name which I once bore and engrave it as an epitaph on the brow of that pictured me that they beheld; let them leave it there in peace, and let them not speak of it again. For a name is no more than that, an epitaph. Something befitting the dead. One who has reached a conclusion. I am alive, and I reach no conclusion. Life knows no conclusion. Nor does it know anything of names. This tree, tremulous breathing of new leaves. I am this tree. Tree, cloud; tomorrow, book or breeze; the book I read, the breeze I drink in. Living wholly without, a vagabond.

My most heartfelt thanks and affection to everyone who read, is reading and will read along with me this never easy, sometimes outdated, always profound book. My each new read stay with you and encourage reflection and self discovery, like it does with me.

As I walk among people now, whether I know them or not, it comes to me that they all see a different me and they all see this moment differently. I won’t go insane, but hopefully will stop imposing my way of seeing this moment on everybody. Or insisting they see me as I see myself. Nice to be free of a bit more of life’s baggage.

Well, I have to admit I can't make a lot of sense out of the inconclusive conclusion. Pirandello has guided us through an experience of different layers of alienation, mostly alienation from what others believe about us, but also from our reputations, our deeds, our words, our properties, and even our appearances in mirrors. There are many ways one can become an object to oneself, for instance when one hears one's recorded voices played back. Since every conscious experience one has is subjective, when one also perceives oneself as just an object among other objects one can get disoriented and can even refuse to admit that that thing is oneself. The extra step that Pirandello takes is recognizing that one can not only be an object to oneself, but is always an object to others. BUT, if one is an object to others, that means there must BE other subjects besides one's own. And that is even stranger. One is not only one object among others, but is also one subject among others.

So I get the sense that Moscarda's confusion arises mostly from the paradox of other subjectivities, not the paradox of his own objective being. He can't retain his sanity as long as there are billions of coexisting universes, each with a different center, a distinct consciousness that is somehow not him. In those billions of universes, he is merely one more piece of furniture, yet he is the center of THE universe—the only universe of which he as any direct knowledge. His solution then strikes me as a cowardly way out: to live in a world untroubled by consciousnesses other than his own, that is, in nature. Walking among flowers and trees he is not seen by another.

Sorry about rambling like this, but I think what I'm saying is that I think Pirandello has done something similar to what Sartre did a few years later: he has given an impressive analysis "the other." Sartre summed it up in the famous phrase from No Exit: "Hell is—other people." (https://www.thecollector.com/jean-paul-sartre-hell-is-other-people/)