This is our last “real” chapter (next week’s can be considered a short epilogue) and arguably the most important plot-wise; it reiterates and confirms every concept Pirandello has been furiously explaining, while at the same time putting into doubt everything we’ve learned about our main character. Your opinion of Moscarda has swayed between sympathy and suspicion, amusement and exasperation. What are you going to think of him when it’s all said and done?

The blame must fall upon me

And nothing was any longer true, if nothing was true, for itself. Each one on his own account assumed it to be so and appropriated it to himself, by way of filling up as best he might his own solitude and conferring some sort of consistency, from day to day, upon his own life.

A lot happens in this chapter, so let us quickly recap the events: Moscarda is contacted by Anna Rosa, a friend of his wife. He doesn’t know the woman particularly well and is puzzled by the summon. He meets Anna Rosa in a convent, and the eerie atmosphere of the building arouse in him an unexpected attraction to the woman. During the meeting, Anna Rosa trips and accidentally shoots her foot with the gun she carries in her purse. Town-wide gossip erupts at the news, and Moscarda is shocked to learn that Dida has long suspected him (or rather, her clueless husband Gengé) of having feelings for Anna Rosa. He ends up spending time with the wounded woman, bonding and sharing his philosophical theories with her. In a moment of weakness—and being certain that she reciprocates his feelings—he embraces Anna Rosa, who in return shoots him.

Are you with me so far?

Let’s now look at an alternative read of the events. Let’s say that Dida was right and Moscarda was having an extra-marital affair with Anna Rosa. Let’s say that the two had been meeting in secret at the convent and scheming to get Vitangelo and Dida separated—for example, by dismantling the bank his father-in-law owns major shares in. Let’s say they fought and a gun was fired. Whose gun? How likely it is for someone to carry a loaded revolver without realizing it? Did Moscarda try to assault Anna Rosa after all?

Pirandello has planted several clues in order to make us doubt Moscarda’s innocent, earnest narrative. From his defending Marco di Dio’s satyr episode to the outbursts toward Dida and the dog, there is an undercurrent of violence in our protagonist that will leave a reader uneasy. The biggest clue yet is the clandestine convent meeting: in his 1923 short story “The Return” Pirandello describes a very similar affair, and if it rings a bell it’s because I’ve already told you about it—the short story is autobiographical and the man betraying his wife was Pirandello’s own father. We could argue that the author chose one of the most formative (and painful) episodes from his past to further indict Moscarda.

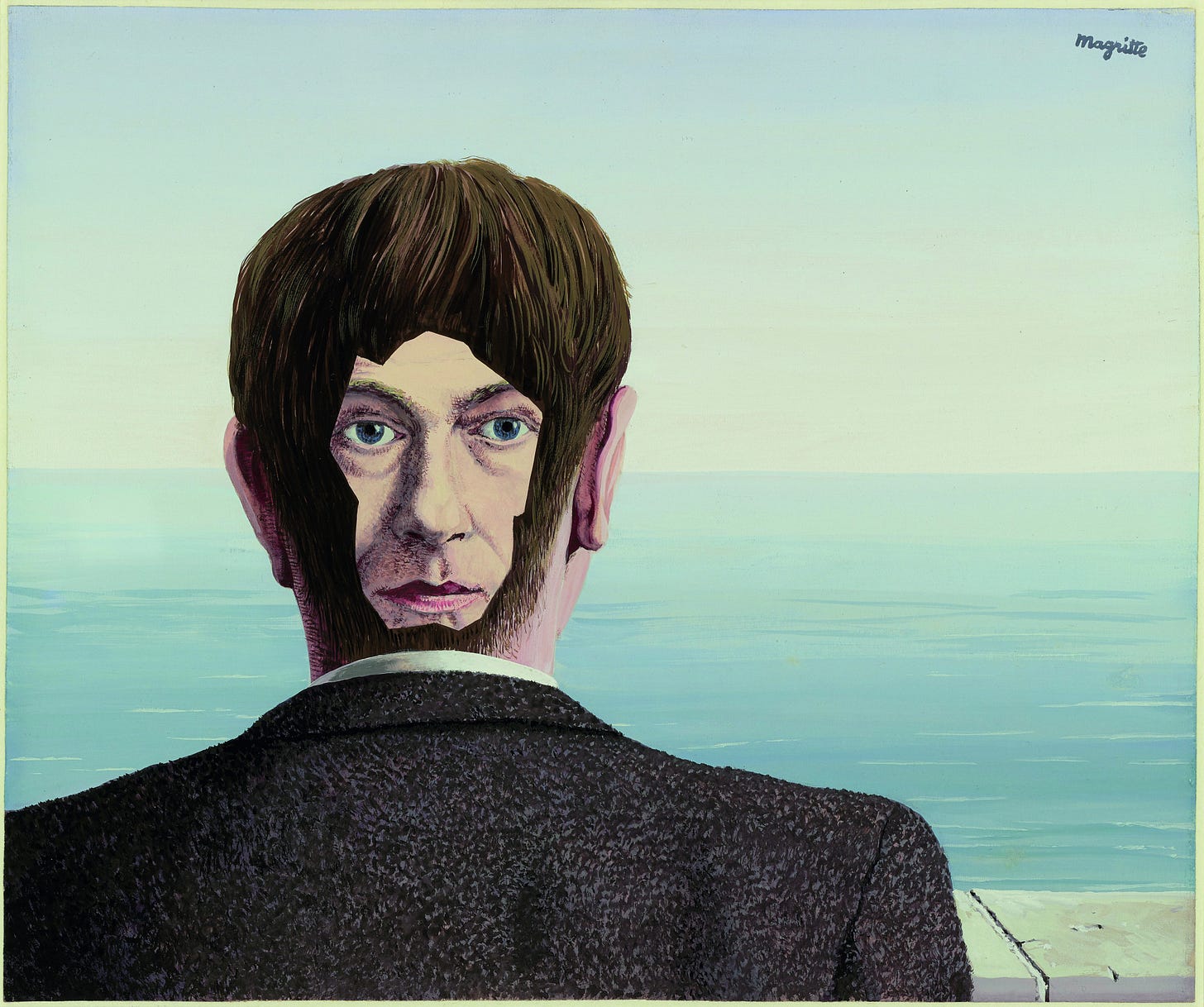

What is the truth, then? Occam’s razor would suggest that the simplest, most obvious hypothesis is the right one. A jury would be inclined to think the same. But as we’ve already been told, justice is only a convention and a jury has no access to absolute truth—nobody has. The events of this chapter are deliberately ambiguous. Moscarda is telling us his version of the truth; maybe he’s sincere, maybe he’s misleading us. Was he an unreliable narrator all along? And could it have been any other way?

How can we ever truly know someone when we have no access to their inner world? No historian, no psychologist, no lawyer, no lover will ever be able to read another’s truth. We can only construct our own stories.

False suppositions, erroneous judgements and gratuitous attributions

It was as if, after having treacherously induced me in all confidence to lay bare my soul, she had thrown wide the door, exposing me to the derision of anyone who cared to enter and behold me thus nude and with nowhere to hide. Appraisals of my family, and judgments passed upon the most natural of my habits, such as I should never have expected of her. In short, another Dida; a Dida who was, in all truth, an enemy.

We've met many alter egos so far, most notably townspeople's Moscarda the Usurer, shareholders' Dear Vitangelo and Dida's silly Gengè. It's time to get to know Anna Rosa's version of Moscarda, that most unhappy Signor Gengè she has fallen in love with, trapped in a marriage with a woman who doesn't understand his brilliance. A tragic figure indeed.

Moscarda is at first appalled by the version of Dida he discovers through Anna Rosa's eyes. His sweet wife, so hating, so callous! How can it be possible? But it is not only possible, it's inevitable, because everyone acts differently around different people. We don one hundred thousand identities around each of the hundred thousands people we meet, and they in turn create their own versions of us. How are we to keep track of who we are supposed to be?

Moscarda losing his sense of identity and believing that his alter egos are real is only apparently funny, only apparently absurd. How can we call our inner self “real” when it’s so complicated, so changeable, so impossible to pin down? And how can we say that the opinions other people form of us are inconsequential, when they can affect our lives so deeply?

For, come to think of it, a thing of this sort is the least of the consequences that may follow from all the unsuspected realities that others attribute to us. Superficially, we are in the habit of calling such things as this, false suppositions, erroneous judgments, gratuitous attributions. Yet everything that may be imagined of us is really possible, even though it may not be true for us.

Moscarda’s sudden need to dismantle the bank is seen as a sure sign of madness by the shareholders, but to Anna Rosa it’s righteous, romantic rebellion, and to the Bishop it’s a symptom of christian guilt he needs to capitalize on. Moscarda’s actual reasons are inconsequential in the grand scheme of things because he will never be able to communicate them, others will always read them according to their own life experience and baggage.

Each famous person’s true motives are lost to history. Each loved one is a stranger to you as you are to them. They are all alone as you are.

A castaway in her solitude and she in mine

I had divined in her an absolute intolerance for anything that showed signs of lasting or assuming stability. Everything she did, every desire that sprang up in her, every thought that occurred to her at one moment, a moment later was ever so far removed from her; and if she felt herself still drawn by anything in the past, this was followed by outbursts of anger and fits of maniacal rage, a complete emotional upset.

Despite being introduced so late in the novel, Anna Rosa is given more attention and depth than any other character, Dida included, and has arguably the most interesting and complicated personality after Moscarda himself. Curious, for someone our protagonist claims he has gotten to know only recently. Almost as if their connection is much deeper than what he's willing to admit.

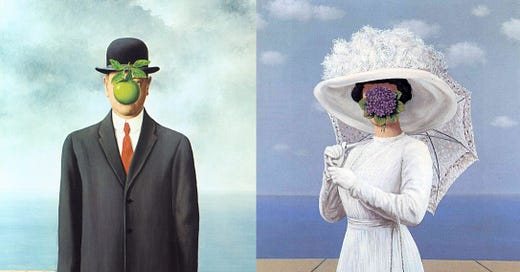

Anna Rosa is a contradictory character, simultaneously easy and impossible to decipher. She's an innocent, naive seductress, a cruel romantic, shallow and proud but lonely and depressed. Like Moscarda, her unusual inner life sets her apart from her peers. She too is an alter ego, a mirror image, identical but quite separate and impossible to reach.

What she forms with Moscarda is a sort of soul connection, and isn't that what falling in love is, the illusion of communication, of companionship? He is able to open up to her and share the inner struggle that has been tormenting him, and she listens and understands. Apparently. She is intrigued by him, attracted to him, repulsed by him, her own personality too shifting and complex to ever translate into what he really needs, as he will never be what she has wished and dreamed for him to be. They seek to capture each other, to encapsulate the other into a perfect puzzle piece they can fit in, and it’s as impossible as to capture someone’s whole personality into a photo. Reaching out to each other, dying of solitude, forever destined to be alone.

And yet, it was she, none other, who conceived the desire to kill me. It came about when, from that satisfaction which I afforded her, and which made her laugh a little, she passed on to a great commiseration for me, by way of charmed response to what she must surely have read in my eyes, as I sat there gazing at her as from an infinite distance and an ageless expanse of time.

Death is a recurring theme in Vitangelo’s and Anna Rosa’s brief, insignificant, world-altering relationship. It’s in all her lifeless photographs, it’s in the gun she carries around, suicide ideations to mirror Moscarda’s madman standing on a balcony, dreaming of flying in a storm. Falling in love is like putting each other in a cage, killing our very souls, and how do we wish and dream of it. Is it a wonder that it all ended with a gunshot?

The God Within and the God Without

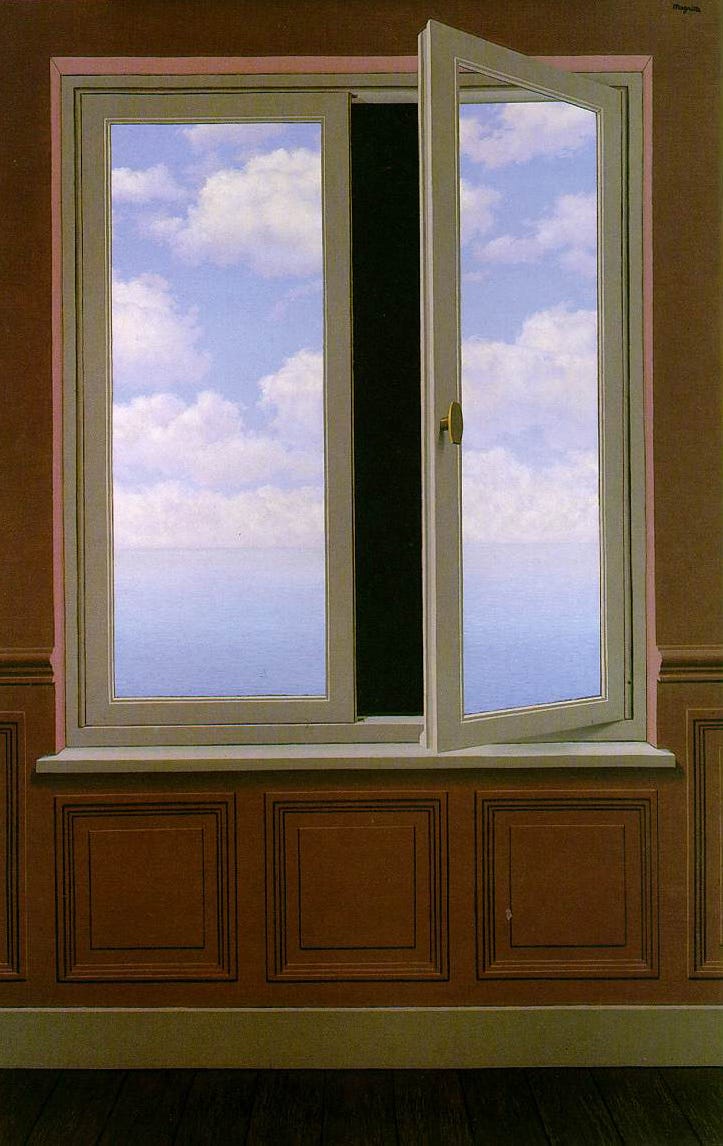

Men—do you understand?—have need of building a house even for their sentiments. It is not enough for them to have those sentiments within them, in their hearts; they want to see them outside, as well, so that they can touch them; and so, they proceed to build them a house.

The house is another recurring theme in the novel. It’s man’s refuge and his cage, a simulacrum of civilization set against a wild instinct for freedom: Moscarda’s house, left unfinished by his father; the bank, dusty and moldy like a prison. In this chapter we visit the Badìa Grande, an old castle turned convent roamed by half-mad nuns. The Bishop’s house, headquarters of unquestionable, righteous faith that ignore the storm raging outside and rattling the windows. The College of Oblates, ancient and crumbling on the outside, airy and gentle on the inside, its inhabitants’ prayers sounding like the pathetic laments of the dying.

Churches are the ultimate house, the ultimate cage, man’s attempt to set the inexplicable into gold and stone, trivializing and corrupting the divine out of fear and out of pride. According to Moscarda (or rather, Pirandello), God can only be found within, in our ineffable soul, speaking truths we can follow but never understand. Our need to decipher the indecipherable, to give an explanation to the impossible and then call it faith, civilization, logic, is freezing our very essence in place, turning it corrupt and unnatural. In short, killing it.

To know oneself is to die.

We leave Moscarda bleeding out on Anna Rosa’s pink fluffy bed. What do you think is gonna become of him? Let’s hear your wishes and your best guesses for the last time.

I found the portrayal of the church fascinating. Mosca seems to contact the more lenient, worldly former bishop with the current, austere one, who will force Mosca’s coming transformation in the public eye to something even more at odds with Mosca’s “self.”

I was quite surprised by the turn of events in this chapter. Up until now the plot has been focused on mostly everyday events with all the interest and intrigue taking place in Mosca’s mind. Then suddenly, we have not one but two gunshots! In a convent! Quite the turn of events. It hadn’t occurred to me that we might have an unreliable narrator on our hands. I would have expected that if he had tried to assault Anna Rosa he would have just blamed it on one of the ‘others’ so he couldn’t be responsible. But your pointing out of the clues was very intriguing! My guess is that our confused protagonist is on a downward slope to ruin. But we’ll see!