Hey gang! I have a smaller entry this week as we relax with a rather uneventful chapter. We’re reading from pages 144 to 161 of the Vintage Classic paperback, and yes, that’s the whole of chapter five. We’re well past the halfway point and slowly but surely reaching the end.

“In the course of a novel, and especially one characterized by tense psychological analysis and quick action, one must grant the reader a few moments of respite. Each great author of lengthy novels allowed his or her readers to take a break: Homer, Dante, Cervantes, Madame de La Fayette included secondary plots. […] Stendhal too added breaks between the action. A simple change in tone gives the perception of rest.”

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa wrote the above for one of his literary classes, and in this week’s chapter he puts those thoughts into action as we leave Prince Fabrizio alone with his woes and follow Padre Pirrone on a quick family visit. Some readers like chapter five, some find it superfluous. What do you guys think, was this a welcomed break or a failed experiment?

Rustic origins

February 1861. Father Pirrone is visiting his hometown, a small village close to Palermo that might as well be in a galaxy far far away, thanks to the state of Sicilian roads of the 19th century. The Jesuit is visiting his family on the anniversary of his father’s death: Pirrone Sr. was a man who practiced the typically Italian and mafioso principle of omertà – in a nutshell, the art of minding your own business, of keeping your mouth well and truly shut whenever you see illegal activity. Thanks to selective mutism and, as we find out later, some little stealing of his own, the dearly departed has died in his bed and left a small fortune behind – at least by peasant standards.

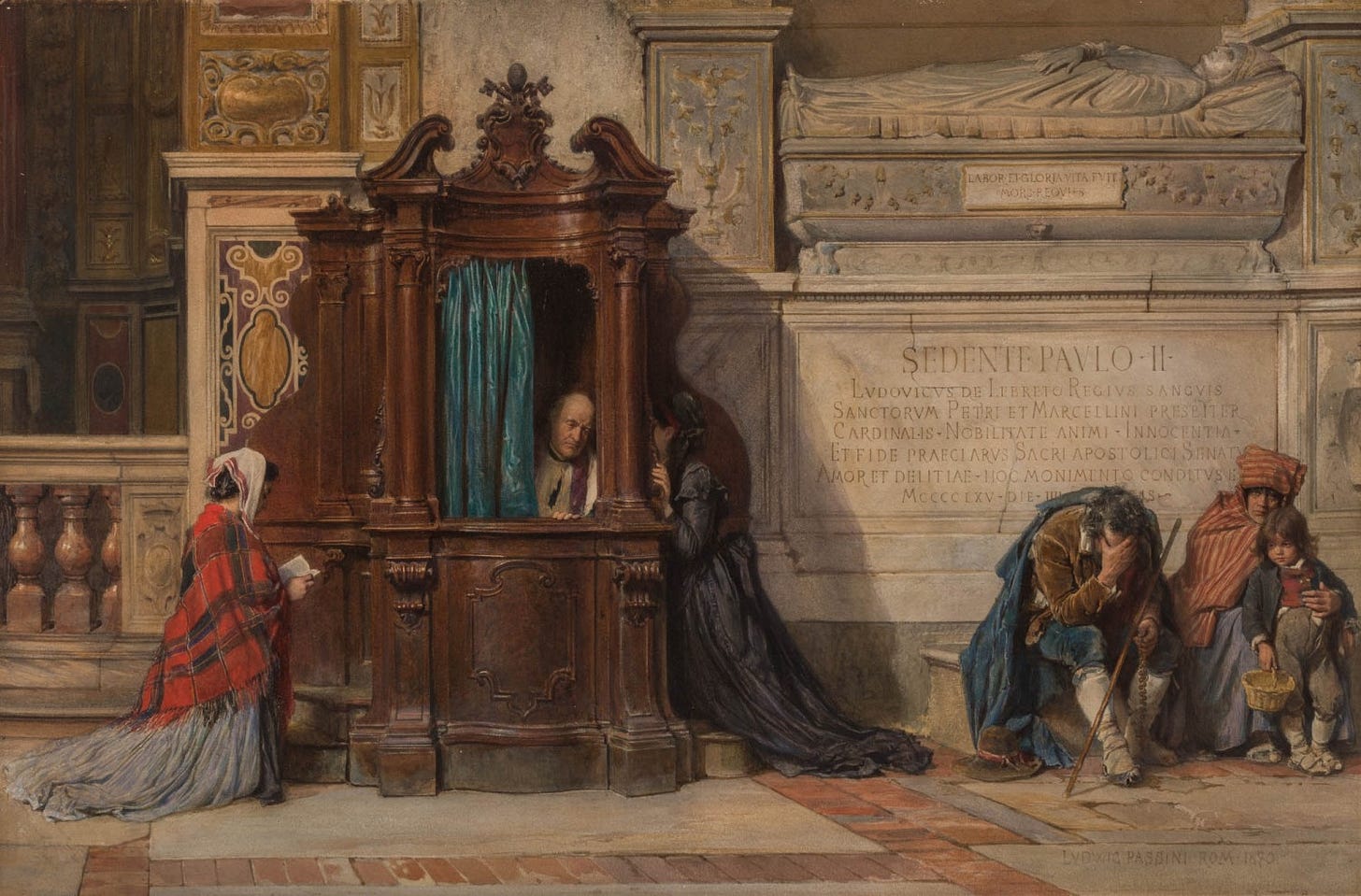

Father Pirrone is almost a celebrity in the village of San Cono, thanks to the splendor and richness of his family (a two-story house, a tiny almond grove!) his proximity to aristocracy and, last but not least, his religious status. In the late 1800s the church was a fundamental institution in catholic rural areas: priests (most of the time) fed the poor, educated children, explained news and laws, negotiated between peasants and governments and between the villagers themselves. Priests spoke Latin! Catholic Mass was still celebrated exclusively in Latin, a mandate that would only be lifted in 1970, and churchgoers learned to chant and repeat prayers in that mysterious language: priests were the only ones who could translate the Word of God for them.

Rapacious state

Father Pirrone, having no love and no hope for the newborn Italian Kingdom, is always game to badmouth the new regime. Friends gathering at his family house bring tales of fiscal bereavement, and one man in particular, Don Pietrino the local herbalist, is appalled at having to pay taxes for the mystical profession his ancestors have been practicing since time immemorial.

“But I go and gather the grasses, these holy herbs God made, with my own hands in the mountains, rain or shine, on certain days and nights of the year. I dry them in the sun which belongs to everybody and I grind them up myself, with my own grandfather’s mortar. What have you people at the Town Hall to do with it? Why should I pay you twenty lire? Just for nothing like that?”

Old Pietrino and Sicilians like him might have eventually accepted the Kingdom, had their taxes been used to improve life on the island. Unfortunately, that was never the case. And what’s more, the poor and peasants resented the disruption brought to the age-old balance between Christianity (Pirrone and his prayers) and paganism (Pietrino and his ritual herbs).

The ‘nobles’: selfish or misunderstood?

Lampedusa through Father Pirrone launches into another one of his monologues, but it seems like his impassioned defense of aristocracy is not as famous as the Sicilian speech from last chapter. I wonder why?

He argues that aristocrats are not so bad after all: they might live by different rules and have different worries than us mere mortals, but they are trying their best to make sense of this life like everyone else. At least they have their good manners and code of conduct differentiating them from modern jackals – or capitalists. Besides, filling the world with palaces and jewels can only improve it, just like building wonderful cathedrals is ultimately a victory for the arts. Royals and nobles have a ceremonial function similar to the Church's, if you really think about it!

But don’t get things wrong. Our celebrated author, despite being a Prince himself, isn't arguing at all that aristocrats are superior people, and indeed he's as quick as anybody to point out when Fabrizio is being insensitive or violent or selfish, when he mistreats those around him, when he falls pray to sloth or lust or pride. Lampedusa, depressed and pessimistic as usual, believes that all people are equally bad and equally doomed. You and I might think that a society where a few hoard money and power while others starve is deeply unjust. He thinks that trying to change anything is a pointless dream: get rid of kings and others will fill the void. And after all, don’t king and peasants cry just the same?

‘Ncilina

It’s difficult to stomach teenage Angelina being described as a bitch in heat, a slave to her future husband. It’s difficult to read about her mother, Sarina, crying in terror anticipating the violence her husband is capable of. Lampedusa is bleak and unforgiving with them as he is with everyone else, but it stings more when the women are so clearly victims of the male pride and violence that engulfs them.

“Once assured of the imminence of ’Ncilina’s marriage, the “man of honour” showed complete indifference about what her behaviour had been. But at the first mention of the proposed dowry his eyes rolled, the veins in his temples swelled and the lurch in his walk became more marked; from his mouth came a gurgle of low obscene oaths and announcements of murderous intentions; his hand, which had not made a single gesture in defence of his daughter’s honour, began clutching the right pocket of his trousers to show that in defence of his almond trees he was ready to spill the very last drop of other people’s blood.”

The parallels between the two 17-year-old brides, Angelica and Angelina, are self-evident. Both experience lust for the first time on a hot November day. Both young husbands chase their bodies and dowries rather than their love. Father Pirrone, believing himself superior to such matters, reflects bitterly on how both couples, the rich and the poor, are equally born from ugliness and greed.

Even a chapter that is arguably lighter and filled with irony becomes poisoned with the author’s bleakness. The houses and streets of a idyllic hometown are rich with nostalgia as well as misery, dirt and manure. Young lovers are shallow, relatives are greedy, fathers are abusers. Only in nature one can still find some beauty and compassion; the wind blows strong and true and the stars shine bright but too far to give any warmth.

Next week we’re going to a ball! We’re reading all of chapter six (from pages 162 to 182), and it will be meatier and juicier than what we had today, I promise.

Till next time!

This chapter was fascinating. It gave depth to the priest and what a marvelous herbalist! No wonder the souther part remained in poverty.

I liked how Pirrone, when faced with a woman pregnant out of wedlock is not moralising (as you might imagine of a man of the cloth) but utterly pragmatic.

How interesting - that quote you included at the top from Tomasi about giving readers a break. I've been wondering about Pirrone and the role he plays in the story. He seems like an important auxiliary to Fabrizio somehow. And both appear to be 'dying breeds' as the saying goes.