We’re finally at the most famous (and personal favorite) chapter: the ball. If you watched the movie, you probably remember Burt Lancaster dancing the waltz with Claudia Cardinale in that gorgeous white dress. In my opinion, the movie fails to capture both the lyricism and the utter sadness Lampedusa achieves with this chapter, but I’m curious to hear your opinions on it! And to our American friends: I’m sorry to drop this one during Thanksgiving weekend, make sure you’re well rested before tackling it.

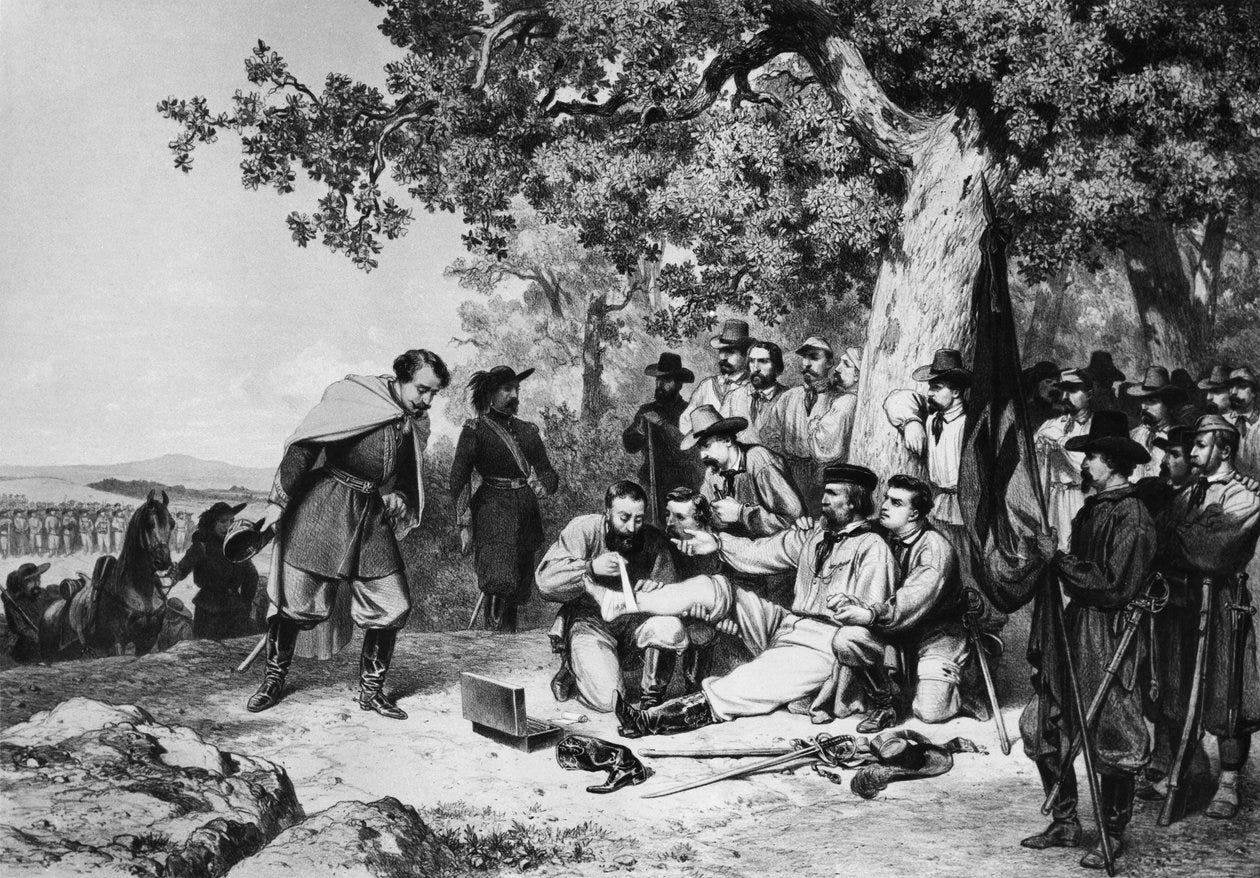

The Battle of Aspromonte

The Fanfare of the Bersaglieri, Italy’s most famous war march, doesn’t have any official lyrics. Yet when Bersaglieri soldiers storm the streets with their trumpets, everyone knows what to sing: Garibaldi was wounded / He was wounded in his leg / Garibaldi is leading / He’s leading the battalion. / Garibaldi was wounded / He was wounded at Aspromonte / It’s written in his face / He’s looking for revenge.

By 1862, Rome had been declared Capital of the newborn Kingdom of Italy. There was one small problem: Rome hadn’t been conquered yet. Pope Pious IX was still ruling over his ancient feudal lands, and his main ally, the Emperor of France Napoleon III, watched over him like a hawk, ready to intervene at the first sign of war.

Garibaldi and his Redshirts were growing impatient: after defeating the Bourbons and annexing southern Italy, targeting the Pope was the next logical step. The Kingdom of Italy, spread thin in an effort to fight back banditism and rather afraid of France, had categorically forbidden Garibaldi to continue his solo mission. But did Garibaldi listen? No, no he didn’t. He was an idealist hellbent on a mission, and he had at his command a ferocious private army crying “Rome or death!” The Italian government had no choice but to try and intercept him.

On August 29th, 1962 the Redshirts faced the regular Italian army in a particularly impervious area in Southern Italy called Aspromonte, “rough mountain”. Garibaldi did not want to fight, he hated the idea of killing fellow Italians and knew personally many of the soldiers that were now facing him. He deployed his 1500 men on the battlefield but, when the enemy advanced, he suddenly ran in front of the troops and yelled, “Don’t shoot! These are our brothers!” Some men shot anyway, many froze on the spot. In the confusion that followed, two bullets hit Garibaldi’s hip and foot.

The battle was over ten minutes after it started, with only 15 casualties. Garibaldi was carried to a nearby forest and assisted by three different surgeons. As he sat under a chestnut tree with his leg being bandaged, Colonel Pallavicini, commander of the Italian army and the very character we are about to meet in this chapter, approached him. He bowed, he kissed Garibaldi’s hand, he softly spoke to his ear, pleading him to surrender. Garibaldi let himself be captured.

It would be another 8 years before Rome was finally taken.

A salutary warning

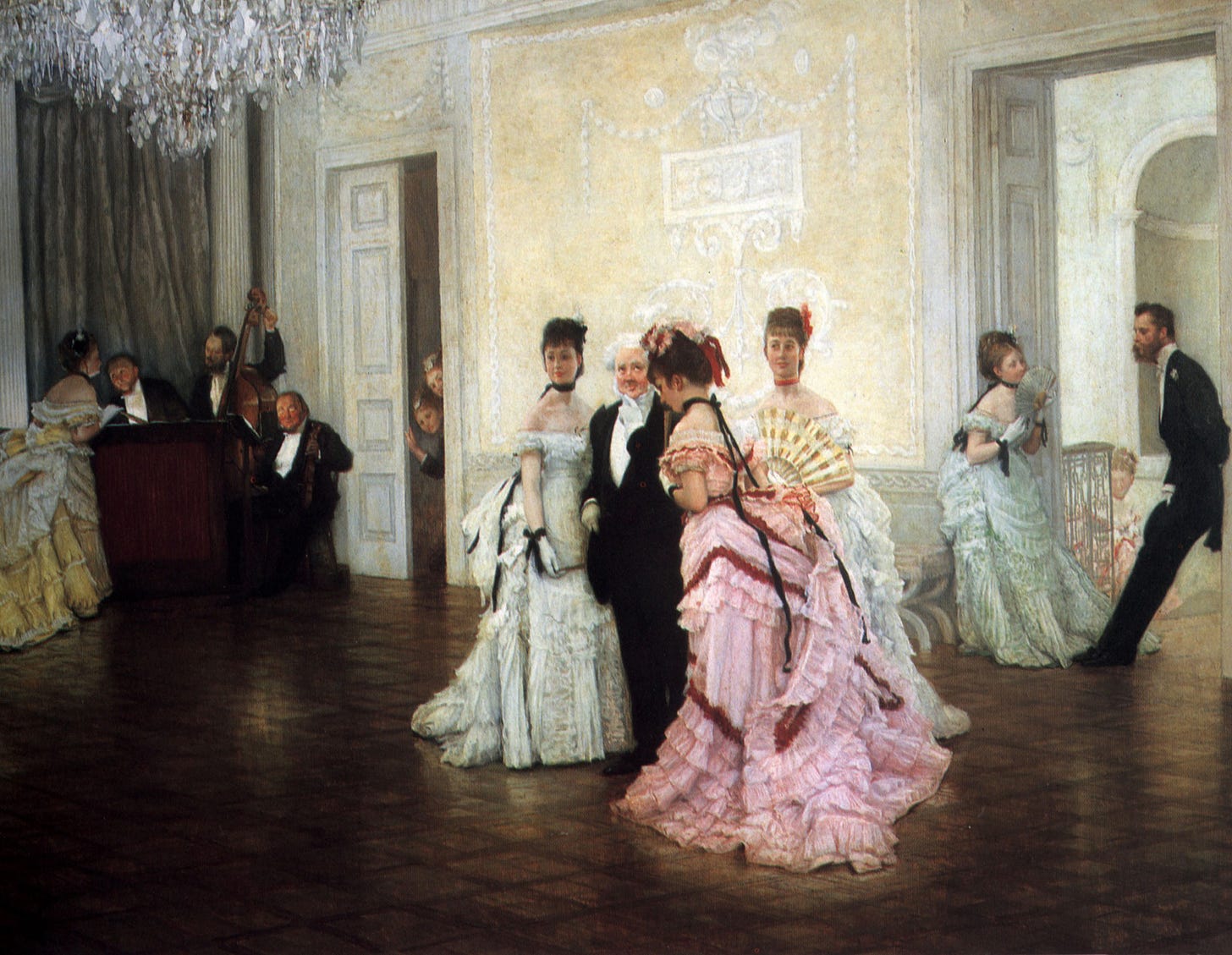

Two years after the revolution and annexation, the aristocracy in Palermo has settled enough to go back to their favorite pastimes. It’s the night of the biggest ball of the season and we’re treated with plenty of delightfully dry and amusing vignettes: a carriage crammed with too many crinolines, grandchildren spying from the nursery, the awkwardness of arriving too early, dancing shoes and scented mustaches, Angelica gaining an artsy reputation with her backhanded compliments. Even the gaggle of girls that Fabrizio mercilessly describes as monkeys in a zoo is downright hilarious, and I inordinately enjoy picturing girls in pink puffy silks dangling from chandeliers.

Alas, this is Lampedusa we’re talking about, and we know by now that happiness and beauty cannot exist in his world without the complement of ugliness and grief. The tone of the night is set early when the Salinas come across a priest on his way to perform the viaticum, or Last Rites. This is the most obvious memento mori yet, but while it casts a large shadow on the ball, there is still a glint of light in the dark, as a child following the priest through the black, silent streets of Palermo is ringing his bell in delight. Life in death and beauty in decay in a never-ending circle.

The jewel box

Fabrizio, like all true introverts, is soon uncomfortable and can scarcely believe his own daughters find balls entertaining rather than exhausting. He roams from room to room, increasingly annoyed at the superficiality and vapidness surrounding him, and it’s worth nothing that his loneliness is a byproduct of his pride.

The ball is a prime example of Lampedusa’s use of opposite images. It’s described as a jewel box sealed against the terrors of the night, gilded and glistening but rotting from the inside, inhabited by the usual ghosts and relics and people on the edge of extinction. The artificial scent of flower vases clashes with the wild breezes of Donnafugata, the gloriously opulent meal is made of slaughtered animals and plants born of manure.

As his usual, Fabrizio’s irritation turns into melancholy and self-pity. He watches the young couples on the dance floor and can only see their future demise. Once again his yearning from eternity works as a sort of time machine. Fabrizio won’t ever let himself exist in the present: past and future are chasing him from opposite but equally bleak directions. And so the paling gold of the palace is a tale of long-lost glory. So Pallavicini prophetizes of Blackshirts, and the gods on the ceiling are bombed during World War II.

“Neither was good, each self-interested, turgid with secret aims; yet there was something sweet and touching about them both; those murky but ingenuous ambitions of theirs were obliterated by the words of jesting tenderness he was murmuring in her ear, by the scent of her hair, by the mutual clasp of those bodies destined to die.”

Fabrizio watches Tancredi and Angelica and sees Romeo and Juliet, perfectly selfish, perfectly in love, perfectly unaware that they’re actors in a tragedy. Tenderness for his fellow human beings overcomes him. Superficial and cruel and maddening as they may be, they are his brothers and sisters in the calamity that is being alive.

“Even the female monkeys on the poufs, even those old boobies of friends were poor wretches, condemned and touching as the cattle lowing through city streets at night on their way to the slaughter-house; to the ears of each of them would one day come that tinkle he had heard three hours before behind San Domenico. Nothing could be decently hated except eternity.”

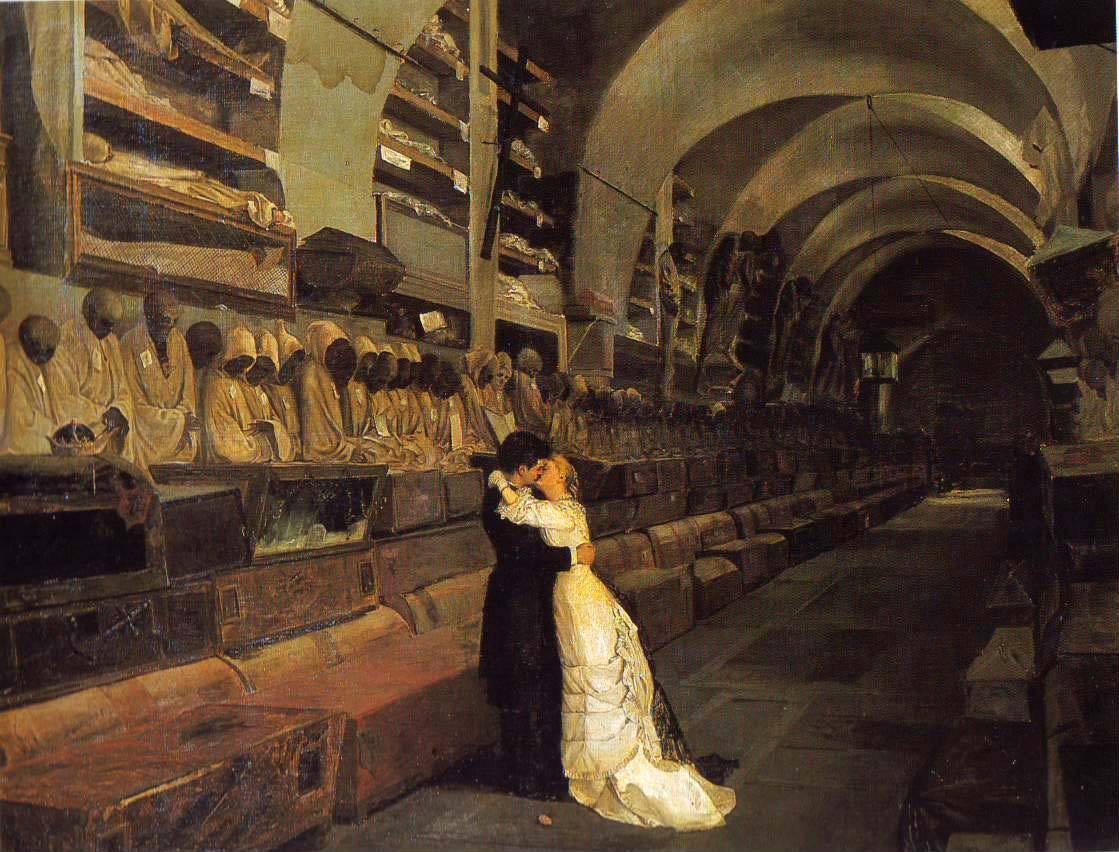

Fabrizio jokingly wishes his body could be placed in the Capuchin Catacombs like in olden times. This is an actual place (and tourist attraction) in Palermo where, starting from the 1600s, mummies were placed in rows, sitting or even standing up, dressed in their sunday best and waiting for their living relatives to visit. Yes, this is a thing people chose for themselves. The mummies are around 8.000, there are mostly monks but also soldiers in uniform, girls in wedding dresses, plenty of children. I’ve added a painting but DO NOT look for actual pictures if you’re faint of heart.

Something that happens to others

Hiding in the library, Fabrizio contemplates an old man dying in a painting and, inevitably, his own future death. Something is finalizing in him, the search of temporary oblivion has almost turned into a longing for an eternal one. Since we’ve known him Fabrizio has been yearning to sleep, to forget, to transcend the world’s troubles. Now that the “safety exit” is in sight, what troubles pained him are starting to look inconsequential.

“As always the thought of his own death calmed him as much as that of others disturbed him: was it perhaps because, when all was said and done, his own death would in the first place mean that of the whole world?”

“If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.” That’s the most famous sentence in The Leopard, the one that perfectly describes the essence of the book. Or does it? Can an infinite paradox be put in such finite terms? Fabrizio will die, and the world will keep spinning without him. And also, Fabrizio will die and the whole world will be gone, because he will no longer be there to witness it.

Tancredi finds his Nuncle in contemplation of the painting, jokingly asks whether he’s courting Death and doesn’t know just how apt he’s being. Fabrizio reflects wistfully on the way Tancredi, Angelica and all young people seem to look at death: as something other, distant, something that could never happen to them. Isn’t that a (misguided) kind of eternity too? The young always feel immortal.

And then, a little miracle happens that night. As small and maybe just as futile as the boy ringing the bell in the dark, but moving nonetheless. Fabrizio dances the waltz with Angelica and, for maybe five minutes, he is young and immortal again. Life in death, in a never-ending circle.

The long night is almost over. The gilded rooms are stained with smoke and sweat and urine. On the streets slaughtered animals, no longer feeling, begin their final journey. And up there in the sky, Venus is always watching.

If you thought this chapter was a bit of a bummer, boy do I have news about next week! You can already guess by the title. We will be reading chapter seven, that is from pages 183 to 193. And I’m going to remind you that this is a book by a man with a terminal illness reflecting on his own mortality, so if that’s a difficult subject for you be prepared and be kind to yourself.

Till next time!

How did the ladies manage those puffy dresses when they had to use the chamber pots or whatever?

I could relate to The Leopard. At 72 I am being left behind as culture changes quickly, my stamina is no longer as it was, I leave gatherings to let the younger ones mingle, etc. One last dance—how wonderful for him.

Ah, this was my favourite chapter too Ellie. How incredibly beautifully and subtly written it is. I really loved the evolution of Fabrizio's mood. His irritation and desire to be elsewhere, slowly modulating into a feeling of deep compassion for the people there gathered: 'Don Fabrizio felt his heart thaw; his disgust gave way to compassion for all these ephemeral beings out to enjoy the tiny ray of light granted them between two shades...'

And Fabrizio's sense of his own finitude is beautifully juxaposed (as you mention) by Tancredi and Angelica who are in love and out of touch with mortality, playing the parts of Romeo and Juliet without knowing that the 'tomb and poison were already in the script.'

Earlier, before his heart thaws, Fabrizio rather chillingly observes the black clothes of the men dancing and it reminds him of 'crows veering to and fro above lost valleys in search of putrid prey.' You point out that death is present everywhere for him - in the appearance of the priest performing last rites, in the men like crows, in the painting in the room Fabrizio withdraws to. But his attitude changes from viewing those present at the ball as disgusting and base animals infected with mortality to seeing them more kindly.

(Also, loved (as always) the paintings you collected together in this post :)