The second to last chapter of The Leopard is comparatively short, but it packs quite the emotional punch. It deals with death and mortality on a very intimate level, I invite you once again to approach it with care if you know it’s going to especially affect you.

The usual masks

The characters in The Leopard often prophesize the future, and it’s both apt and extraordinary that Lampedusa managed to predict his own death: he was also traveling to consult a doctor, and he died on a July day too, far away from home, with his family at a strange bedside.

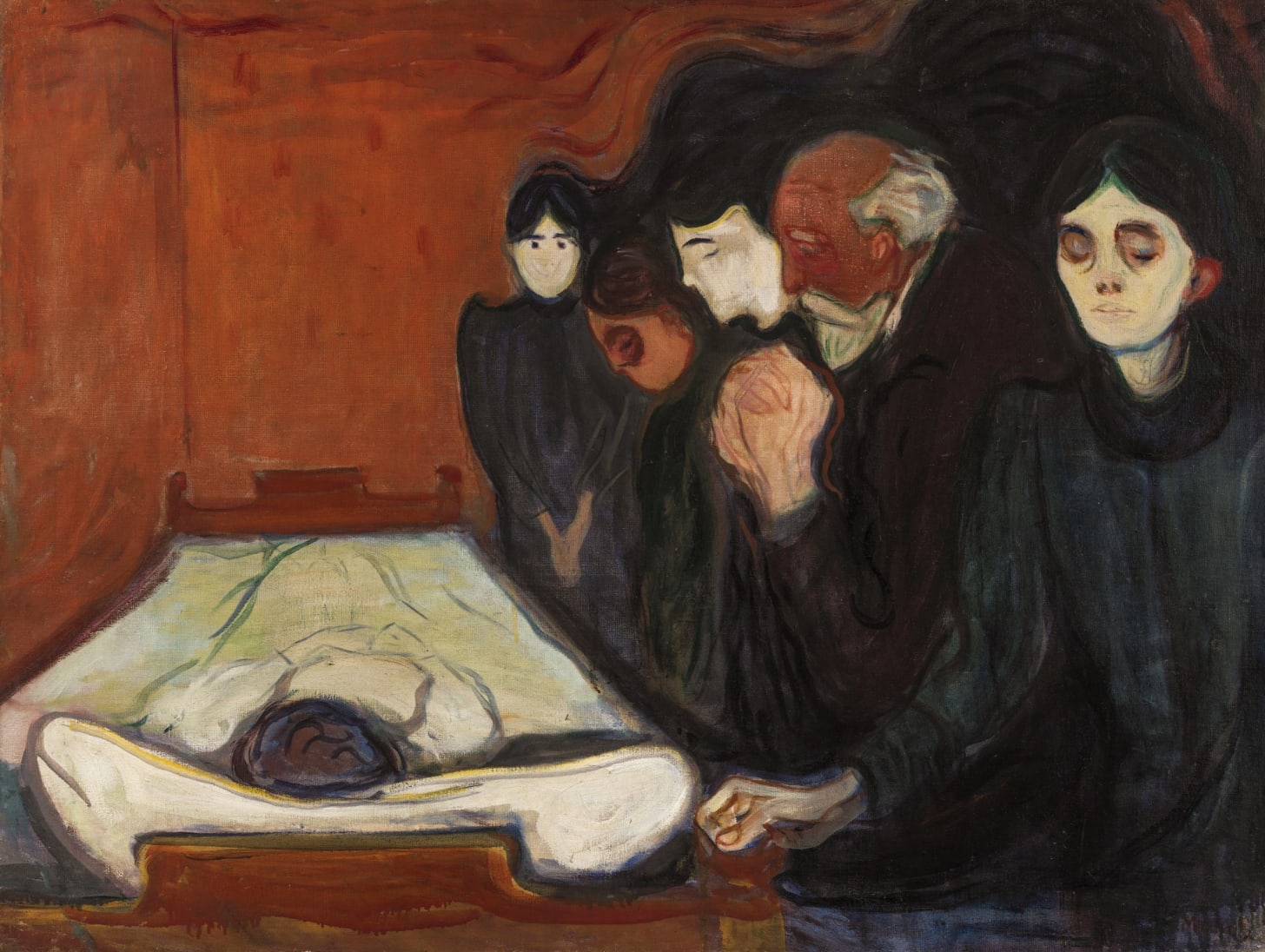

Twenty-one years have passed since the ball in Palermo and the waltz danced with Angelica. On a sweltering afternoon in 1883, Fabrizio dies in a hotel room, so close and yet so far from his own home. Before we approach him, let’s catch up with the familiar faces crowding his death bed. If you paid attention, you’ve already guessed everyone’s fate.

Tancredi is now an established politician with a bowler hat and a 40 year old wife. Concetta is still unmarried. Paolo, the boring eldest son, was killed by one of his beloved horses. Giovanni, the son who fled to London, never came back home, forgot his roots and became a businessman like Sedàra. Some other faces are missing: Maria Stella, the Prince’s wife, died from diabetes. Father Pirrone is long dead too, and so is Bendicò. Fabrizio’s latest dog will look for him in vain in the villa’s garden.

We are introduced to a new family member: Fabrizietto, the youngest grandson. I have no idea who his parents are, we only know that he has a double dose of Màlvica blood. Barely mentioned in the book, Màlvica was Fabrizio’s cowardly brother-in-law, which means that one of his children has married a cousin; Fabrizietto seems to be yet another product of incest. Named after his famous grandfather but reduced to a derogatory nickname, Fabrizietto watches the dying with open curiosity. His grandson’s dull, mediocre personality is to Fabrizio ultimate proof of the end of the Salinas.

The journey

Fabrizio has reached Palermo for the last time by train; the grueling day-and-a-half journey mirrors the one he took to reach Donnafugata all those years ago. But what was once just a vague feeling of doom is now a proper funeral procession with Nature as the only constant protagonist, cruel in its typically indifferent way, with lunar landscapes scorched by the over-present, tyrannical sun. The locomotive is a dying horse struggling up a hill, the blinding sea that faces Fabrizio from the hotel balcony is a dog cowering under the barrage of fire from the sky.

Fabrizio is now a husk of the imposing man he used to be, he’s a tall corpse with the strength and independence of a newborn. He needs to be fed and cleaned by family and by strangers, the ultimate humiliation for a man as proud as him. He no longer has it in him to complain, he’d rather dedicate his last moments to introspection. Besides, he wants to play his part til the very last. If a Prince must be sent off with Christian rituals, then so be it. And if the dead must be shaved by the undertaker, he’ll resign himself to it too. Why can’t he just look like himself, he wonders, why does God condemn the dying to change so radically, to lose their human features?

He doesn’t own anything anymore. His house is unreachable, Donnafugata is a distant dream. His objects will lose all memory and all purpose. His grandchildren already live in a radically changed world. The only thing he has left is his own emaciated body, and that’s about to go too. He thought the Leopard, with all his history, strength, wealth and pride, could keep living after his own death. He was wrong. Everything has changed.

The sea storm

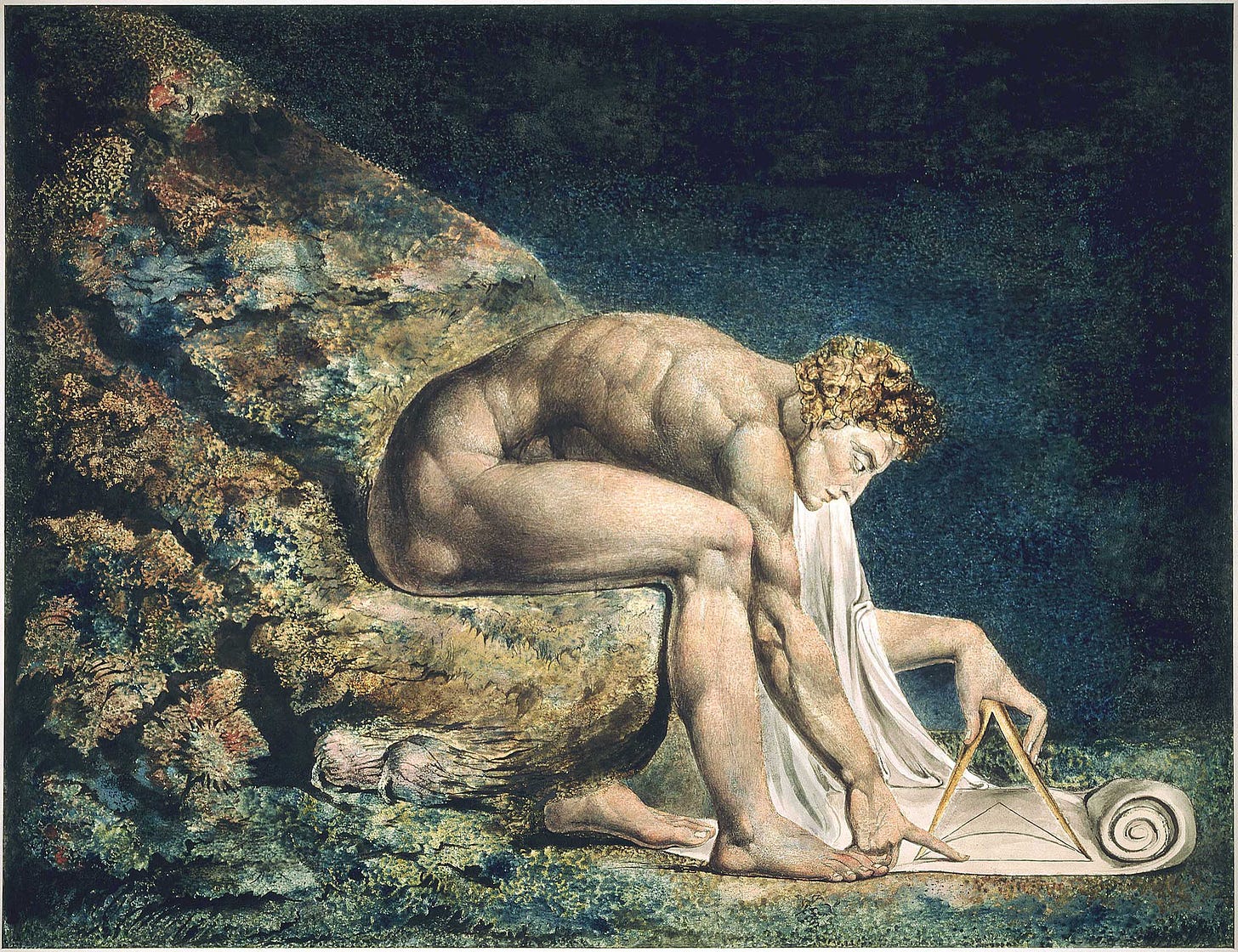

Fabrizio compares the inevitable passage of time to an hourglass steadily losing sand, each grain that left his body accumulating who knows where. Is it his soul that he’s losing? Or is it just a matter of physical entropy? He used to be proud to know about the hourglass, wiser than other men, more aware of his own mortality. It sounds so silly now.

As the end approaches, he realizes that it isn’t sand leaving his body after all, but something far more ephemeral and precious: it’s water. The healing fountain, the well of many uses hated and beloved by Siclians, giving life and taking it away with every drought and every flood. It used to be a few droplets evaporating, now it’s tall, crashing waves and he is an exhausted man on a draft, about to be swallowed whole. Our wannabe Neptune was never going to be king of the seas. He no longer listens to his family, he can only hear the deafening roar of the ocean leaving his body like through an open wound. He is so old and tired, how can there be still so much life to lose?

The balance sheet of life

Even on his death bed Fabrizio is a mathematician at heart, and in his final moments he endeavors to calculate how many happy days he’s had during his whole life. There are very few, golden flecks between the ashes of sorrows. A month or so of married life, very few hours with his children, a few more with his dogs. Brilliant Tancredi, of course, the privilege of having him as a nephew. Some academic achievements, some happy hours shooting in the windy plains of Donnafugata. And all the nights he spent studying the skies, does that even count, he wonders? Should he have tried to live life to his fullest, instead of forgetting himself in his hobbies?

In the growing dark he tried to count how much time he had really lived. His brain could not cope with the simple calculation any more; three months, three weeks, a total of six months, six by eight, eighty-four … forty-eight thousand … √840,000. He summed up. “I’m seventy-three years old, and all in all I may have lived, really lived, a total of two … three at the most.” And the pains, the boredom, how long had they been? Useless to try and make himself count those; the whole of the rest; seventy years.

The sum of his happy days is depressingly small, but what else could we have expected from a depressed man? And what about you? If you were to die tomorrow, how many days did you truly live? Is there any point in trying to change that now? Lampedusa, as always, doesn’t think so.

The Morning Star

The water leaving him turns into an ocean, the waves are foaming and, as the legends say, life is born from that foam: it’s Venus of course, the pagan goddess of love. And it’s planet Venus, the morning star, the very girl Fabrizio has courted in those endless nights behind the telescope. Tancredi was right, he had been courting Death herself.

Venus pushes in between the group of mourners. She’s a pretty young thing in a traveling coat, rather sexy too, and in love with Fabrizio. Do we hold his lust against him, or do we shrug at this unrepentant old man? He just Confessed himself too, but like he said, the only sin worth mentioning is the Original one. He dies the way he was born: flawed until the very end.

Venus takes Fabrizio by the hand and leads him into a train carriage. The last moments of delirium? Or did he really get to see his beloved stars? Maybe out there in the icy cosmos his soul will finally be at peace.

We only have a chapter left! Any guesses or hopes on what it’s going to be about?

Thank you so much for following me this far, and till next time!

This was a sad but elegant section. And what a marvelous metaphor for death, the losing of water, returning to the oceans from which we evolved, the primordial sea.

I've fallen a bit behind due to my commitments. But I'm checking in to say that I'm reading, currently on chapter 3, but I'll finish by the end of the year. And your articles are wonderful.