Happy weekend Leopard gang, and welcome to chapter two. This week we’re reading from pages 35 to 44, starting from the beginning of the chapter and ending with the line “and from that moment, invisibly, began the decline of his prestige.”

The conquest of Sicily

We left the Prince and his family on May 13th 1860, just as General Garibaldi’s army was landing on their shores. It’s now August and the Salinas are going on vacation. Yes, we skipped all the excitement, aren’t you disappointed? Fabrizio is denying us the battles and the blood, almost censoring them, inviting us to pick up a history book or a swashbuckling novel if we really want to concern ourselves with such unsavory business.

We’ll have to learn what really happened on our own.

On May 5th, around 1,000 Redshirts had “stolen” two steamships in Genoa. The world knew and pretended not to see, everyone was secretly rooting for Garibaldi to put an end to the obscurantists Bourbons, anonymous donations of money and weapons had arrived from all Europe.

The ragtag army landed in the city of Marsala on May 11th, protected by two British warships that were “accidentally” in the neighborhood. (If asked, the British will deny it.) They headed to the mainland and quickly doubled in size thanks to Sicilian volunteers that joined en masse. Most of the Bourbon defense army was miles away, holed up in Palermo. On May 14th, seeing that the people were on his side, Garibaldi declared himself Dictator of Sicily. He continued his advance, easily winning every battle. The Bourbons retreated and retreated, with the population revolting against them.

When they reached Palermo on May 27th, the Redshirts were 4,000. The city was once again uprising and fought alongside them. They advanced street by street, pushing against a much larger, barricaded army, as Bourbon warships bombarded them from the bay. Still, they couldn’t be stopped.

The enemy surrendered on May 30th. When the siege ended, Garibaldi pardoned all Bourbon soldiers (after all, they were Italians too) and appointed a provisional government, with himself as Dictator. Land was assigned to the volunteers that had joined him in battle, pensions to the widows of those who had died.

The world rejoiced. Money and reinforcements arrived from all over, workers as far as Liverpool and Glasgow were fundraising for them. People of all sorts, politicians, journalists, intellectuals, were gathering in Palermo to witness the miracle. Alexandre Dumas Sr. arrived with boxes of weapons and champagne to celebrate his old friend Garibaldi, and left us historically invaluable photographs of the barricades still standing in the streets.

By August 1st the Redshirts were more than 20,000 and had conquered the whole of Sicily, a legendary, heroic feat that is now part of Italian lore. An utter farce, according to the Prince of Salina.

The victors

Where was Fabrizio during all this? Safe in his villa on the outskirts of the city, listening to the bombs go off. As we saw in the last chapter, he had made some backroom deals to protect his property and, the unpleasantness of battle over, he sat slightly annoyed at his fellow citizens. Those same people that were loyal to the Bourbons a week ago were now jumping on the bandwagon, parading around with the victors and praising Garibaldi to the skies. Or rather, “the Dictator”, Fabrizio won’t stoop so low to say his name. Of course he’s been doing the exact same thing, it’s the inelegance of his peers he finds unsavory.

But he had to admit that all this was a mere surface manifestation of ill-breeding; the fundamentals of the situation, economic and social, were satisfactory, just as he had foreseen.

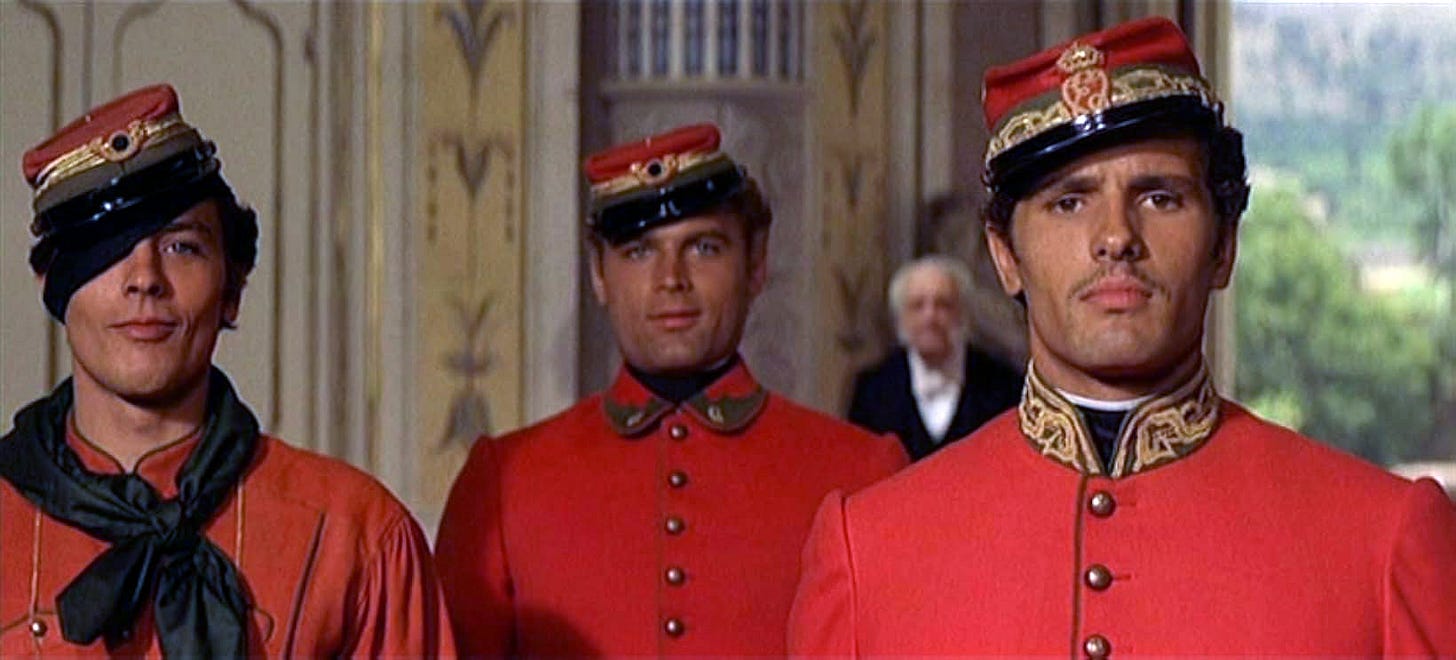

In another smooth flashback we witness two Redshirts visiting Villa Salina. Their demeanor thoroughly reassures Fabrizio: they’re aristocrats like himself and they address him with the respect he’s entitled to. The encounter is idyllic, as he puts it. Two delightful, polite youngsters singing arias and talking poetry, with a side of teen angst courtesy of daughter Concetta. Are we suddenly in a romance novel?

To Fabrizio everything is theater and people are divided between those who can see it, like himself and Tancredi, and the gullible and naive, like these two young men. They think themself heroes that brought freedom and democracy to faraway lands. And yet all it took was some money and connections to protect Father Pirrone from Garibaldi’s anti-clericalism, to secure the Salinas’ precious vacations in the countryside. Victory and glory are just words; bribery, corruption, entitlement make the world go round. People are people and nothing has changed, the snake is still biting its own tail. If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.

The waters of life

One thing that has changed (inconsequential to Fabrizio, like all that has happened in Palermo), is the painting that hastily replaced a portrait of old King Ferdinand. It’s The Pool of Bethesda, a place of miraculous healing mentioned three times in the Bible.

Now there is in Jerusalem by the Sheep Gate a pool, which is called in Hebrew Bethesda, having five porches. In these lay a great multitude of sick people, blind, lame, paralyzed, waiting for the moving of the water. For an angel went down at a certain time into the pool and stirred up the water; then whoever stepped in first, after the stirring of the water, was made well of whatever disease he had. (John 5:2)

In Italian, Tomasi calls Bethesda with its other name, the Probatic Pool or “pool of the sheep” (from the Greek probatĭcus), a name derived by the customary washing of sheep about to be sacrificed in the Temple of Jerusalem. Healing and life born of innocent blood, and we’re once again reminded of the dead soldier, gutted like a lamb, feeding the life in the garden. Fabrizio is still dismissing the sacrifices of many so he can enjoy his little pleasures, his country estate, his daily morphine. As long as the battle is far away and the lambs are hidden in the kitchen.

On their way to Donnafugata the Salinas come across a well of many uses, an oasis of rest and refreshment in the Sicilian desert.

“Next to the main farm building a deep well, watched over by those eucalyptuses, mutely offered various services: as swimming pool, drinking trough, prison or cemetery. It slaked thirst, spread typhus, guarded the kidnapped and hid the corpses both of animals and men till they were reduced to the smoothest of anonymous skeletons.”

Water, bringer of life and healing, brings death and decay that will feed more life in return. The five carriages gather around the well, recreating the five porches of Bethesda.

Across the desert

We’re back at the beginning of the chapter, following the Prince and his family as they trudge along the apocalyptic landscape that is rural Sicily.

“All round quivered the funereal countryside, yellow with stubble, black with burnt patches; the lament of cicadas filled the sky. It was like a death-rattle from parched Sicily at the end of August vainly awaiting rain.”

While people like Tancredi (too young and brazen) and Father Pirrone (too secure and relaxed) are unaffected by their surroundings, Fabrizio as usual internalizes it all, coloring the environment with his own troubled thoughts. Again the sun and heat bring stupor and oblivion and Bendicò has to chase away funereal omens. The metaphor of life as an endless journey through nothingness is spelled out in the text. Night, as we already saw, brings demons that only daylight can exorcise for fourteen hours or so.

“These early morning fantasies were the very worst that could happen to a man of middle age; and although the Prince knew that they would vanish with the day’s activities he suffered acutely all the same, as he was used enough to them by now to realize that deep inside him they left a sediment of sorrow which, accumulating day by day, would in the end be the real cause of his death.”

A day will come when no woman, no constellation, no charming town will be powerful enough to escape the pain that is dripping bit by bit, building up like sand in a hourglass. Fabrizio told us that his daily activities are a mere palliative to escape his own mortality. He is Bendicò, with a name in the past tense.

Storybook town

Donnafugata in Italian means fleeing woman, another name with troubled undertones. A typically Sicilian toponym, it’s a mispronunciation of the Arabic “Ayn Al-Sihh at” meaning healing fountain—isn’t that a coincidence? Donnafugata is more morphine for Fabrizio, a magical, nostalgic place where time has stopped and he’s still the all-powerful feudal lord of old.

If some things have changed here too, Fabrizio is doing his best to ignore or dismiss them. There’s a new mayor sporting the Italian tricolor, don Calogero Sedàra (remember that name), but that’s about it. Some patriotic graffiti that are almost faded, or rather, that he’s mentally pushing back into the walls. Fabrizio has refused to tell us what happened during the Siege of Palermo, and now he censors what is happening in Donnafugata, as he’s welcomed by firecrackers exploding all around like gunshots and the overpowering music of Giuseppe Verdi, the most emblematic artist of the Italian Resurgence. They’re playing La Traviata, the story of a dying courtesan struggling to find true meaning and love after a life of frivolity.

Among the small gathering in Donnafugata the only honest spirit is organist Ciccio Tumeo (as symbolized by the dog with him). Everybody else is playing a part, the new arrivals dusty but imposing, the authorities gleaming but humble, Tancredi the folk hero wearing his now useless eyepatch like a prop, Fabrizio the benevolent king, looking like a sated and pacified lion, almost like he’s just made love to Mariannina. He’s basking in the adoration of his subjects, refusing to see until it’s too late that things have indeed changed. The people of Donnafugata, maybe for the first time, are seeing him for what he really is, a colorful character in a play about to end. The king is naked, long live the king.

“Over the great solid yet staved-in door a stone Leopard pranced in spite of legs broken off by flung stones.”

And that’s all from me. Next week we’ll read until page 55, up to the line, “and with these words the haughty noble to whom rain would only be a personal nuisance showed himself a brother to his roughest peasants.” Let me know if something isn’t clear, I blab and blab and I’m afraid I’m gonna confuse you more than anything. Would you like me to keep things more straightforward?

Till next time!

Three days being covered in white dust, over 120 degrees inside the carriage, wearing all those proper clothes, good grief, I wonder why The Countess and the daughters don’t try to overthrow the prevailing, also. Or perhaps, they, too, believe that the more things change, the more they stay the same. So much description of decay but so far, decay is not fertilizing the future.

(Don't change anything Ellie! I am really enjoying these posts!)