The Leopard: a long-winded introduction

In which we step on the sunny island of Sicily and meet an unlucky author.

(Please note that I’m no historian, geographer or a certified expert on anything, really! This entry is supposed to give you only a general knowledge re: our book’s themes. We’ll go into more details in the coming weeks, but consider yourself encouraged to explore these themes further if you find them interesting, it is a fascinating subject.)

The OG melting pot

Sicily, the biggest island in the Mediterranean. A tiny strait separates it from Italy; cross a slightly larger strait and you’re in Africa. Greece is right there beyond the Ionian sea. Sicily is the ultimate Mediterranean crossroad, a strategic spot where different cultures were always bound to meet and trade and melt. A warm, fertile land, smack in the middle of ancient trade routes. Sicily was an impossibly alluring prize for its neighbors.

The first colonizers were the Phoenicians. Then came the Greeks, then Romans, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Byzantines, Muslims, Normans, Germans, French, Spaniards. By the 1800s, Sicily had been under foreign rule for at least twenty-five centuries, and Greek temples sat next to Mosques sat next to Norman stone cathedrals. Sicilians sang like Arabs, cooked like Greeks, painted like Dutches. What does it do to a people, being colonized for so long? Our book struggles with that very question, as yet another invading force looms on the horizon.

Enter the Redshirts

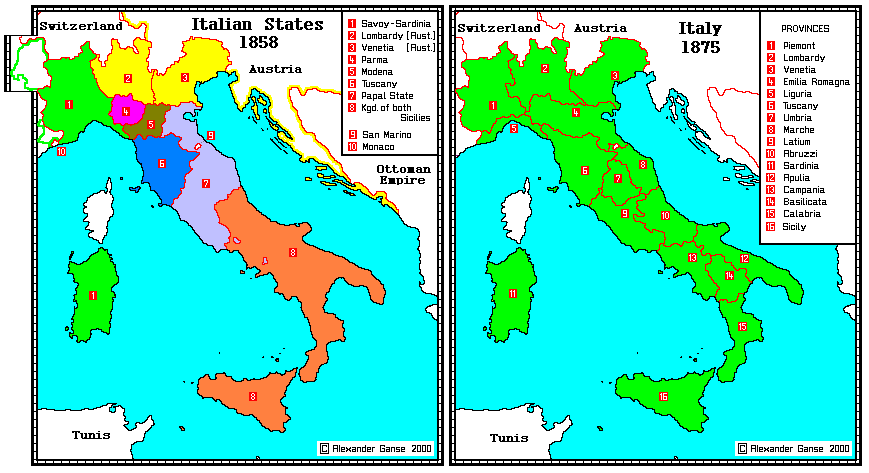

In the year 1860 a sovereign state, the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, covered the whole of southern Italy. Despite its name, the capital was way up in Naples and the (anachronistically absolute) king was a Spanish Bourbon. Things were about to change fast.

Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy, from his fancy palace in northwest Italy, was eyeing his colleague’s throne. Empires were out, cool new concepts like independence, revolution, patriotism and nationalism were sweeping over Europe and South America (I know, I know, we were late to the party.) If Italy gets to be independent, thought old Victor, why shouldn’t I be its king?

The main obstacle to Victor’s dream, believe it or not, was His Holiness the Pope, who still ruled over his lands, the Papal State, like an old feudal lord. Taking Rome by force was a bit of a faux pas, the Pope being head of the Catholic Church and all. France, for one, wouldn’t have liked that. Victor Emmanuel had to find an alternative route.

Enter General Giuseppe Garibaldi, folk hero and owner of quite the nice beard.

Revolution was like catnip for Garibaldi. He had already fought for independence in Brazil and Uruguay, perfecting guerrilla warfare. He was followed across continents by his own volunteer army, a ragtag group wearing Uruguayan red shirts. This colorful bunch, around 1000 of them, landed in Sicily on May 11th 1860, and thus the Expedition of the Thousand began: a feat of heroism celebrated to this day. Sure, there was some raping and pillaging, but history is written by the victors or, in this case, by Victor Emmanuel. (The Savoyard king was keeping his distance, in case things didn’t go his way. Those dastardly Redshirts?! Never heard of them!)

Sicily was annexed with a curious mixture of bloodshed and fanfare. Garibaldi marched north; Rome fell a few years later. Italy as we know it today was born.

A 20th century prospective

One Mussolini and two World Wars later, Sicily was still struggling. On paper, Sicilians were citizens just as much as their Italian counterparts. In practice, they were on average much poorer, illiterate, discriminated, plagued by mafia (which is not as cool as Francis Ford Coppola made it seem).

Giuseppe Tomasi, Prince of Lampedusa, Duke of Palma, Baron of Torretta and Montechiaro, Grandee of Spain, was neither poor nor illiterate. Rather shy, prone to depression, he was born in 1896, had fought in World War I and, upon his return to Sicily, had dedicated his life to books. He spoke French, English, Spanish and Russian and had a deep understanding of European literature. He never wrote much himself except a bunch of notes for his lessons (he was fond of teaching classes on Joyce and Goethe and everyone in between), plus a couple articles on literature criticism.

Until.

In 1953, at age fifty-six, Tomasi traveled to a conference, where he got to speak with some of the most influential Italian writers of the time. Back home, he disappeared inside his study and began writing The Leopard. Somewhat based on his own great-grandfather’s diaries, the book was set during those months of upheaval in 1860, and achieved a unique blend of fiction, family chronicle, autobiography, historical investigation and social analysis of the beautiful, difficult island he loved so much. A story about past Sicily that undeniably spoke about present Sicily.

Tomasi toiled for three years and emerged in 1956 with a few chapters that he shyly presented to his wife and close friends. Encouraged by them, he sent copies to several publishing houses and was painfully rejected, over and over again. He had bared his soul on those pages; rejection broke his heart.

If he could only have waited. In 1958 The Leopard was finally published, and by the 1960s it had grown into a worldwide phenomenon. Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa didn’t see any of it. He died on July 23rd 1957 of lung cancer in a faraway city, never knowing he was about to become as celebrated as those authors he studied all his life.

What on earth is this book?

Pinning down The Leopard to one literary genre has proved impossible. In fact, scholars can’t even agree on what kind of animal a “gattopardo” is! The Italian title is an obscure word describing the rampant cat depicted on the Tomasi crest of arms, but which cat? Our English translation chose the leopard, the French one went with a cheetah; it’s a tiger in Finnish, an ocelot in Dutch and a lynx in Japanese. Heraldry experts say it’s the smaller, long-eared serval.

Just as its title, the novel contains multitudes. It’s both homage to and bitter satire of patriotic pulp novels, it’s historical and anti-historical. Prince Fabrizio of Salina, our main character, is identical to the author’s own great-grandfather, prince Giulio Fabrizio Tomasi, down to his leonine features, German roots and love for astronomy. As for the rest of the family, he didn’t even bother to change their names. Is it biographical? Yes. No. It’s personal, it’s growing with the memory of your ancestors, sleeping in their houses and playing with their trinkets. You’re making up a story, but is it really fantasy if you lived it? Or are you transferring your own experiences to the long dead? Many have argued that the lonely, stern, skeptical Fabrizio is nothing but autobiographical.

Ultimately, it’s up to each reader to decide. Next Saturday we will meet Fabrizio and the gang, I can’t wait to hear what you think of them. Remember, we are reading up to the line, “anxious to show it had forgiven the silly interruption of a fine job of work” (page 7 of the Vintage Classics paperback edition.)

Have I rambled enough? My English can be a mess, please let me know if something isn’t clear. Is this your first time reading The Leopard? Have I changed your expectations? Let me know what comes to mind, and see you next Saturday!

Just picked up my copy today, and had never heard of this book until you mentioned it in Simon's chat a few weeks ago! Looking forward to my second foray into Italian literature and second read-along/slow read (go Simon/W&P!), and learning more world history. Thanks for doing this!

Thanks for this Ellie. Have dug out my copy and looking forward to getting stuck in.