Holy Mary, Mother of God,

pray for us sinners,

now and at the hour of our death. Amen.

We begin at the end. The end of prayer, the end of the day, the end of life as we knew it. Revolution is brewing, the old nobility will soon be replaced by new ideas and new money. “Nunc et in hora mortis nostrae,” a little memento mori to celebrate the occasion.

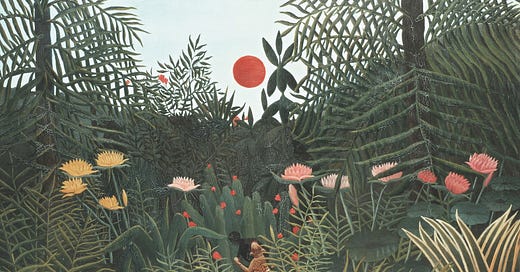

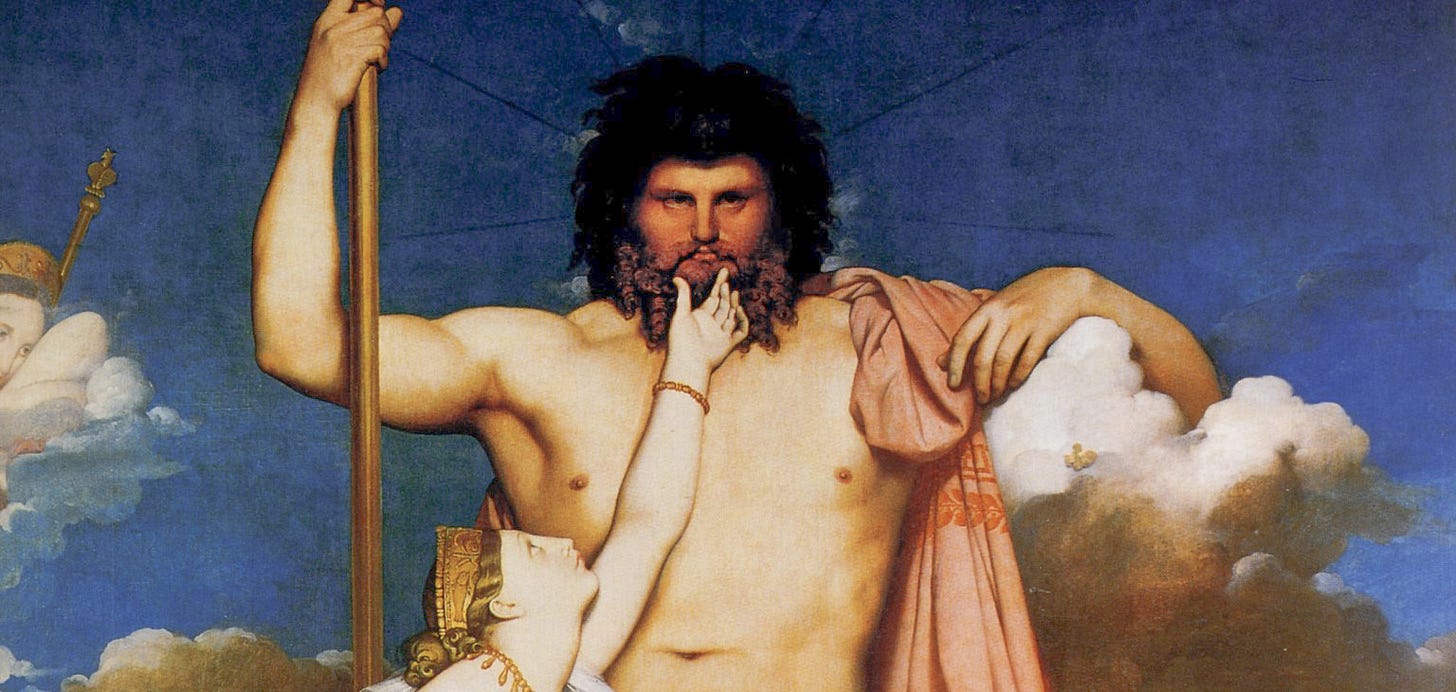

The Salina family doesn’t quite catch the symbolism. They just finished their tedious daily Rosary, reciting with diligence “some unlikely word, love, virginity, death.” Unlikely, unnatural, repugnant– the frescoes seem to think so too. They seem to stir all around the family, these painted gods, as undeniably alive as the people in the room are dead; a pagan relic of steamy rococo times, long replaced by more puritanical (the British would say Victorian) sensibilities.

Ignoring all rules of prospective, the unlikely pantheon comes together in a jumble of naked limbs: they kiss, they tease, they peek under the long skirts of ladies and priests, reflecting back the dreary souls of the living like bizarre –yet familiar– carnival mirrors. (Can’t you just see our author, small Giuseppe Tomasi, following them with the eyes of a child, showing his tongue at monkeys and parrots?)

God of paradoxes

The king of all heavens, a knockoff Jupiter shipped from the plateaus of Mount Olympus, at present looks down on the more provincial Conca d’Oro (golden conch), the valley where the city of Palermo sits. He himself, Prince Fabrizio of Salina, is as solid and mighty as his marble tiles and heavy chairs. The room shakes when he gets up. His head hits chandeliers in the houses of mere mortals. Even his prayer book is huge.

He also shields his knees from the floor with a dainty handkerchief. A stain on his broad waistcoat can sour his mood. Fabrizio is an oxymoron, just like the drawing room with “its usual order or disorder”. He’s not fat, he is large and strong. His giant paws are used for caressing women and telescopes. He’s a gifted mathematician slowly but surely going bankrupt. A big inflexible German among diminutive, carefree Sicilians.

Between the pride and intellectuality of his mother and the sensuality and irresponsibility of his father, poor Prince Fabrizio lived in perpetual discontent under his Jove-like frown, watching the ruin of his own inheritance without ever making, still less wanting to make, any move towards saving it.

Add Teutonic austerity to Mediterranean hedonism and leave it to breed under the blazing sun: what could possibly go wrong? Fabrizio, for one, seems to be stuck in his ways, paralyzed by two conflicting natures. Except, the rot goes further back. If you read my Introduction to the Leopard, you’ll know that Sicily itself is a haphazard mix-and-match of very different civilizations; our Prince is only the latest embodiment of the Land of Contradictions.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s slow down to a relaxed Sicilian pace and follow the author into the garden. Let’s observe that glorious and tragic soil.

The beast in the jungle

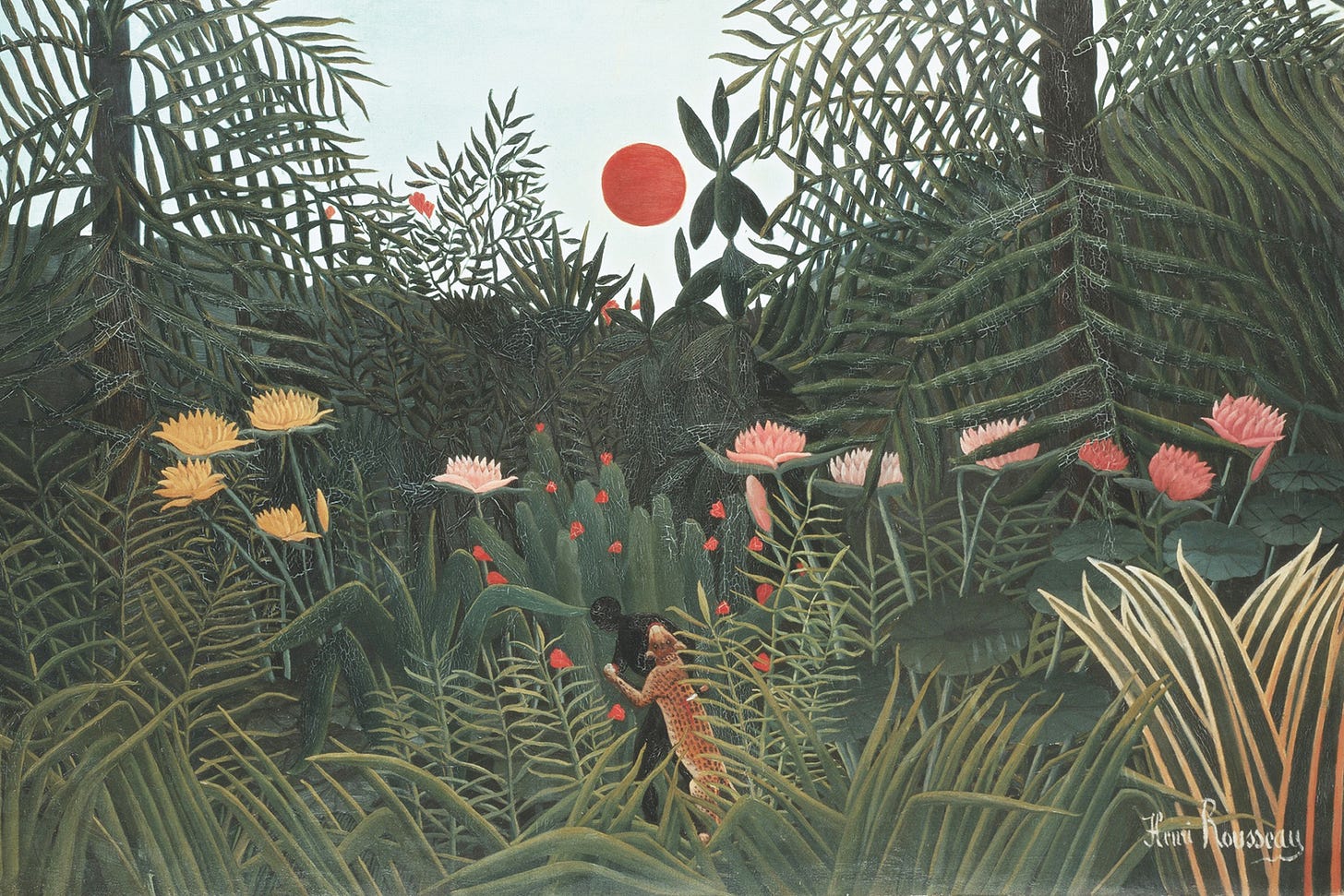

Enclosed between three walls and a side of the house [the garden’s] seclusion gave it the air of a cemetery, accentuated by the parallel little mounds bounding the irrigation canals and looking like the graves of very tall, very thin giants.

The first impression of the garden is chilling: it looks like a graveyard, an enclosure where once mighty giants lay cramped in narrow tombs. It’s another oxymoron, as those funereal mounds are simply teeming with life. Like the paintings in the drawing room, nature has taken over in a tangle of roots, branches and flowers, ugly but overwhelmingly sensual, each plant emanating a scent so vivid it has its own personality—carnations are peppery, roses are solemn, acacias smell like nurseries, orange blossoms (quintessential wedding flowers in Sicily) have a hint of eroticism. Notice how Tomasi’s sumptuous vocabulary enhances the images he’s painting.

And then there’s those Frankenstein roses:

First stimulated and then enfeebled by the strong if languid pull of Sicilian earth, burnt by apocalyptic Julys, they had changed into objects like flesh-colored cabbages, obscene and distilling a dense almost indecent scent […] The Prince put one under his nose and seemed to be sniffing the thigh of a dancer from the Opera.

I’ll say it only once, there’s no adapting how colorful the Italian language is, but even in translation: what a paragraph! The roses, like Fabrizio, have been implanted in strong if languid Sicilian soil, have been stimulated and enfeebled (paradox after paradox), just like the Leopard walking the garden they have mutated into a moody, sluggish, sexy beast.

The garden is both a macrocosm of the Prince’s soul and a microcosm of the island of Sicily, exploding with life and haunted by death, stuck still in the middle. Because we always circle back to death, don’t we? The living are evoking it under the frescoes; sweet scents in the garden grow putrid; the tangle of life grows from flesh long buried underneath.

Toy soldiers

L’Opera dei Pupi is a renowned school of puppetry that stages heroic poems from the Carolingian cycle, think Charlemagne, Roland, Paladins and Saracens. The comparison between those idealized, romantic knights and the dead soldier under the lemon tree is self-evident; the metaphor of the broken toy, a puppet spilling its stuffing on the ground, is shocking.

The object is described in grisly but lavish detail. Death is disgusting and unnatural. Death is natural, death fits in the garden. Bodily fluids seep into the soil, nurture the plants, join the countless who have fed the roses before. Death, to the living, is an abomination. "Or maybe it’s only me,” thinks Fabrizio. The women seem content with one more prayer, the men dismiss it with patriotic nonsense. Why did we allow a boy to get gutted like a pig? Was the puppet ever alive, or was he already a thing, even before the strings were cut? If there’s a moral answer to the conundrum, he can’t find it.

Were people around Fabrizio really so heartless? Was the bleakness he experienced universal or personal? Who is talking to us, an unbiased historian or a suffering poet? Here’s a fact to ponder about, the boy in the garden wasn’t really a Bourbon soldier killed during the riots of April 1860; he was a German soldier, killed in August 1943 by the Allies storming Sicily. Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa was there, he saw the body, smelled it, heard someone say those same words, about a kid who was a Nazi, his guts spilled under a tree.

Those swine stink even when they’re dead.

Reader, would you have felt sorry for that boy? Would you have spat on him too? Fabrizio, or rather Giuseppe, has no answer to give you.

And now for something completely different

Let’s finally talk about happier things, a ray of sunshine in all this bleakness: that super precious dog.

Or is he? (He is, he is, don’t kill me!)

Bendicò the Great Dane is not only the best, most perfect boy; he is, according to Tomasi himself, the key to understanding the whole novel. Why do you think that is? I’ll give you one hint: his name, “Benedicted”, is in the past tense. Based on all you’ve seen so far, how do you think Bendicò fits in? How should we read him? Let me know your theories in the comments, and keep an eye on him from now on.

You guys, thank you, thank you all for the words of encouragement you sent me these past two weeks, I wasn’t sure anyone would be interested in the first place! I’m both scared and elated to show you what I’ve been working on. If I can only transmit a tenth of my love for this book, I’ll call it a victory. If you want to stick around, next week we’ll read from pages 7 to 18 of the Vintage Classics paperback edition, up to the line “Towards dawn, however, the Princess had occasion to make the sign of the Cross.” Here is a (sort of) schedule for you to follow, and here is a character list that I’ll update as we read on. If you have any questions don’t hesitate to ask, I am BURNING to be of help.

Till next time!

Thank you for such an engaging article and for selecting concise excerpts for discussion! It's a lifesaver—I even read more at the beginning. You've written brilliantly about the main character, portraying him as an oxymoron.

I noticed that they begin by reading the Sorrowful Mysteries, which includes Jesus' prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane before his execution. This parallels the dead soldier who died alone in another garden. While we can't equate the soldier's death with an execution, the disregard for his body and how the memory of his tortured form haunts Fabrizio seems to continue the Sorrowful Mysteries motif. Fabrizio's quest to understand "Why did that soldier die?" echoes the question of Jesus' death, albeit on a smaller scale. Was it mere chance that he sought refuge in Fabrizio's palace?

Intriguingly, they pray in a chapel within their palace that features both Christian motifs and the ancient Roman pantheon. After the Rosary, the gods on the frescoes "awaken," as if they had respectfully withdrawn during prayers to another faith. If other deities occupy 23 and a half hours, which ones truly represent the House of Salina? Given Fabrizio's fascination with astronomy, the Olympian pantheon might resonate more—at least Mars and Venus are visible in the night sky.

The garden description is exquisite prose. The notion that everything there aspired to beauty but succumbed to laziness, and that it could only please the blind, paints a powerful image. If it's filled with magical aromas, count me in! Scents are paramount, and their link to memories is unbreakable. It's reminiscent of Proust, who in his books constantly smells his surroundings to evoke memories.

As for the little dog, I'm thrilled if he's the main character and the bearer of the central idea. I have two thoughts: he might guide the narrative, with Fabrizio following him and triggering events along the way. Alternatively, if his name implies he's blessed, perhaps he's the only family member who truly acts naturally, according to his good nature. The others might be influenced by their coat of arms, behaving more like wild cats than Christians. There's even a mention of the dog digging in the garden with the zeal of a true Christian.

I'm glad I joined the reading; I didn't expect such beautiful language and so many images and metaphors. I'm really looking forward to continuing the discussion.

Thanks for your great introduction Ellie. I absolutely loved these opening pages. What a way to start. There's such a heaviness, and rottenness, and sensual energy to them. And the image of the painted figures peeping up the skirts of the ladies (and the *priest*) was wonderful.

I wondered about the paintings "ignoring the rules of perspective" - is the suggestion that these are not very good paintings, ie that this says something about the family being perhaps not as high and mighty (and rich) as they might appear at first?

The description of the garden is wonderful too. I'm reading Daniel Mason's North Woods at the moment, and there's a great image in that of an apple tree growing from a seed in the belly of a dead man which reminded me of these pages. I guess all gardening is like that - decay and regrowth and decay and regrowth. Or vice versa!