Last week: our main character, Moscarda the fly, had a dramatic life epiphany about his slightly crooked nose. How's that for an inciting incident?

This week: Pirandello doesn’t give a fig about the plot and launches into a monologue that is really an imaginary dialogue with his readers. I like to picture him explaining his theories with crazed eyes, grabbing our shoulders and shaking us within an inch of our lives, he’s so eager for us to understand!

The self-sufficing conscience

In the comments you all shared moments in your life when you also felt unsure of your own identity or like you were looking at a stranger in the mirror. We all agreed that it's a common, relatable experience, right?

Wrong! Pirandello says. You might have had similar thoughts as Moscarda’s, but you clearly didn’t follow them to their logical conclusion. You refused, for your own sanity, to understand the implications. And why is that?

You see, each one of us possesses a pesky little thing we call a conscience, a thing that we use to justify our actions. Someone might disagree with you, someone might call you wicked or crazy or wrong, but deep down within yourself you know you’re right. Why, if only people could see things from your point of view! If only they knew what you’ve been going through, then surely they’d agree with you, there is no doubt in your mind about it. It’s comforting, it makes us feel safe and righteous to believe we acted according to our own conscience.

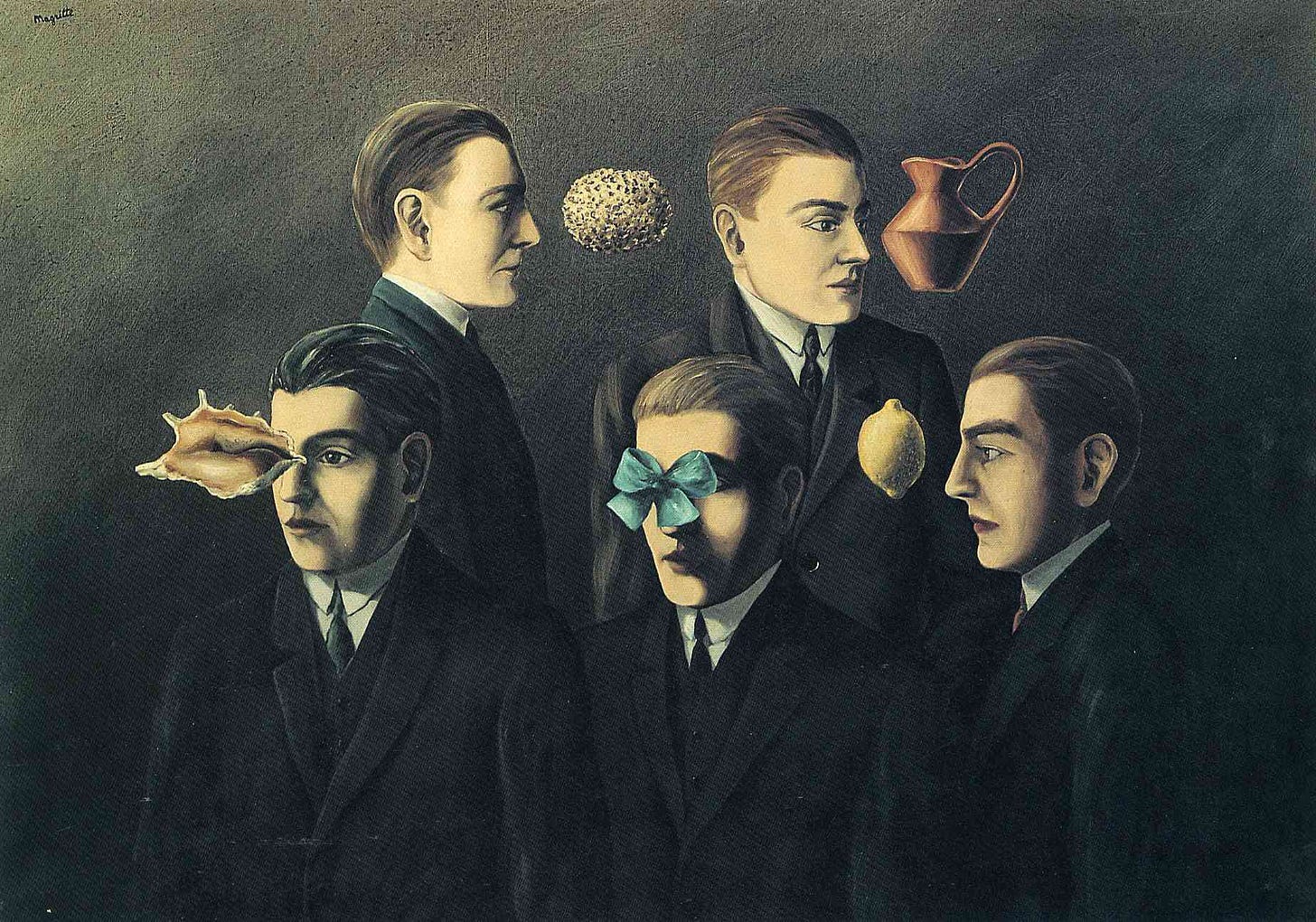

Pirandello argues that to consider our individual conscience an absolute moral truth is our downfall. The champion of all-encompassing relativism, he believes that our personhood (soul, ego, individuality, call it what you will) means nothing. If people understood it, truly understood it like Moscarda does, we’d all go crazy. Our very sanity relies on believing in our own truth, something that, Pirandello screams, is anything but certain or sacred, something in perpetual motion even within ourselves, something that shifts so dramatically depending on who you ask.

Good Lord, why is it then that you insist upon acting as if you did not know it? Why do you insist upon speaking to me of yourself, if you know that, in order to be to me what you are to yourself, and in order for me to be to you what I am to myself, it would be necessary for me, inside myself, to confer upon you that same reality which you confer upon yourself, all of which is impossible?

Who I am to myself and who I am to you are both equally real, solid and valid, Pirandello argues. Which is a bit like saying, they are not real, solid or valid at all. And what is worse, these two people that are both real and not real will never, ever be able to connect or communicate. We are all fundamentally and profoundly alone.

Isn’t that just horrifying?

These beloved objects

But I’m once again getting ahead of myself. Let’s instead follow Pirandello’s simple and pleasant reasoning, he’s better at explaining anyway.

We start with a trivial example. Moscarda’s tenant, an old gentleman, complains about the mosquitoes swarming his house from the old carriage depot. What is a maddening problem to the tenant becomes silly and unimportant in Moscarda’s eyes: he doesn’t wish to clean up the depot, it would be like getting rid of happy memories from his teenage years. Why can’t the man just sleep under a mosquito net? Claustrophobia, you say? That’s silly! Moscarda loves the mosquito net, it makes him feel so safe and snug!

You might want to dismiss this story as Moscarda being spoiled, privileged and inattentive, but consider this: you could have put any other two people in that situation, the result would have been the same. Think about your own landlord, if you have one. Can you honestly say you ever understood each other completely? And what about your employer? What about your family?

Another example. Let’s say Moscarda smashes the fourth wall and goes to visit a reader in his house. The living room is elegant enough, but there’s an old ratty chair clashing with the the rest of the furniture. That’s the chair where the reader’s dear old mom died—it’s sentimental to him, unsettling to most other people.

For it does seem to you that it is, properly speaking, a question of taste, of opinion or of habit; and you do not for a moment doubt the reality of these beloved objects, a reality which it gives you pleasure to see and to touch.

Is your reality more or less valid than mine? Isn’t that chair beloved to you and ghoulish to me, at the same time? Isn’t the mosquito net both a safe haven to Moscarda and a death trap to the old tenant? Which reality do we call absolute, then?

What does the house have to do with it?

When you think about it, objects really are so reassuring and so troubling. Why do we entomb ourselves under a mosquito net or inside a house surrounded by cypresses?1 Why do we build gray geometrical cities where green grass is chased away like a disease? We choose the safety of our houses like goldfinches living in cages of our own making.

Yes, this is a street. Are you really afraid that I may tell you it is not? Street, street. A flint-stone street; look out for the flints. And those are lampposts. Come on; you are safe.

Moscarda Sr. left his house unfinished and uncertain, just like his son’s life. It’s open for anyone to trespass, reimagine and desecrate, and yet Moscarda clings to it like it’s a safety net. And the same courtyard invaded by (what he considers) vulgar hags by day turns into a melancholy, star-bathed desert at night.

We destroy mighty mountains in order to make bricks. We turn century old trees into furniture. We imprison animals to steal meat and fur. We build metal wings, and we only have to step outside the city and look at a real bird to understand how unnatural and infernal an airplane is.

You will quickly re-acquire it there, where all is invented and mechanical, assembling and construction, a world within a world, a manufactured, agglomerate, adjusted world, a world of twisted artifice, of adaptation, and of vanity, a world that has a meaning and a value solely by reason of the fact that man is its artificer.

Clouds and wind

Does the cloud by any chance know anything of the fact of being? Neither do the tree and the rock know anything of the cloud, nor even of themselves; they are wrapped in their loneliness.

We go to the countryside, lie under a tree, look at the clouds. And for a fleeting moment, we are perfectly content. Let-down of nerves, Pirandello calls it, Afflicting need of self-abandonment. Why are trees and rocks and animals happy and we are not, despite all our science and philosophy? When did it all go wrong? The day we stopped being monkeys and became self-aware, he supposes.

In my introduction to Pirandello I’ve talked about the conflict intrinsic to all humans. Simply put, the plight of human nature is understanding the concept of loneliness, its paradox is needing company in a world where everyone is fundamentally alone. Nature is happy because it doesn’t think. Man can only be happy in those rare moments when he abandons himself to instinct and stops thinking. Whose brilliant idea was to give a soul to an animal anyway?

We never stay long in the countryside. We go back in those cages of our own making, we mangle ourselves just like we mangle nature, we petrify our multifaced souls into socially acceptable masks, hoping it will make other people love us, hoping it will make reality seem less chaotic and scary. We invent concepts like morality and religion and call them absolute, and we shun and hate those who question them because our fragile mental stability relies on them being true.

Why do you think it is, otherwise, that firmness of will and constancy of feeling are so highly commended to you? Let the will waver but a little, let the emotions alter by a hair's-breadth, undergo ever so slight a change, and it is good-bye to reality as we know it! We at once become aware that it was nothing other than an illusion on our part.

That dear Gengé

Now we go back to the plot! Now that Pirandello is rubbing his hands in satisfaction after making us all experience existential horror, so kind of him! In my introduction I’ve also talked about the deliberate way he uses humor to make us uncomfortable: Moscarda is a goofy loser putting himself in undeniably ridiculous situations, but the undercurrent of his actions is anything but funny. By making us laugh at a man spiraling towards madness, Pirandello is also making us feel sorry for him. Empathy, the only cure to loneliness.

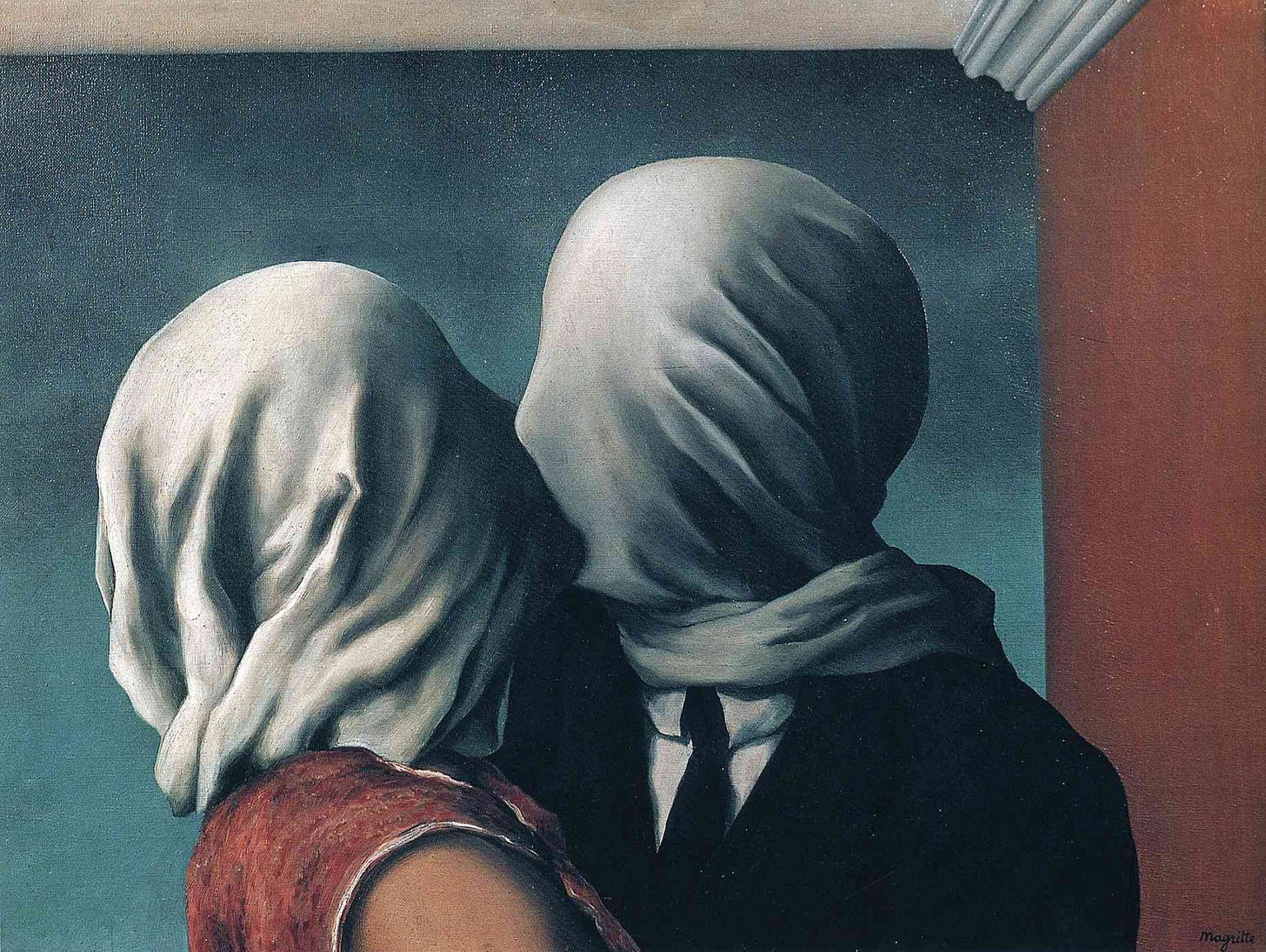

Moscarda’s latest absurdity is as follow: he’s become jealous of himself, or rather, of his alter ego Gengé (pronounced Jen-jay), the man his wife thinks she’s married. Isn’t that just delightful? Imagine that, being jealous of kissing your own wife!

Silly dear, that Gengé. He’s so naive, so sweet, so very different from troubled Moscarda. So very real to Dida his wife. He’s so real, in fact, that the moment Moscarda tries to get rid of him, she thinks she’s lost her husband.

But if Dida thinks Gengé is real, doesn’t that subsequently mean she never meant to kiss Moscarda in the first place? How can we call it true love if Dida and Vitangelo never actually met, if any time he tried to communicate a stranger, that dear Gengé, took over and talked through his own lips? Is true marriage even possible, or is it another one of those relative ideals that we desperately try to call absolute?

I would like to point out another thing: we, the readers, never meet the real Dida. We don’t even know if it’s her actual name, it could easily be a nickname. Moscarda considers her stupid and shallow, a female Gengè, if you will. This silly caricature of a wife is probably nothing at all like Dida would describe herself, but she is real, oh so very real to him and to us, just like Gengé is real to her.

And he was not by any means a puppet. If anyone, the puppet was I.

Who will decide what’s imaginary and what’s not? Who says Gengé has any less right to exist? Who says that when Moscarda tries to kill him, people won’t call him a murderer? We can talk all we want about our right to self-determination, but it’s anything but a given.

Last week

commented that Moscarda’s musings on appearances reminded him of the latest book by transgender activist Jennifer Finney Boylan. Sorry I hadn’t time to reply to your comment, Richard! I’ve appreciated it immensely, but it’s been a busy, crazy week. Consider this my reply: trans issues are indeed serendipitous, in the sense that they illustrate so plainly why the right to self-determination in our society is neither obvious nor universal. Just look at all the parents saying that having a trans child is like having a stranger kill what they considered their real child. Moscarda being guilty of killing Dida’s Gengé is not absurd, not when society wants us to appear and behave a certain way, and there are so many instances when rebelling can and will be considered worthy of punishment.Reading all your comments was truly a treat, it’s an honor to have such brilliant and smart readers. What did you think of this section? I really like it despite the lack of plot, and I’m afraid I babbled a lot more than I should have.

If you’re still in it for the ride, see you next week for Book III!

Mediterranean cemeteries are traditionally decorated with dark, imposing cypresses.

Symbols versus things. We excel all other animals on Earth, as far as we know, in our ability to use one thing to represent something else. Some ways we do that are conventional. Sounds, letters, and brush strokes can be used in ways that feel familiar and friendly. We can each use a word, like 'blue' for example, in sentences and contexts where we don’t question each other. But if someone points at a car I would call 'red' and says, “What a lovely shade of blue,” it will knock me out of my comfortable condition and force me to figure out what went wrong. When they use the word 'blue' in a way that doesn’t make sense to me, I look for an explanation. Did I hear correctly? Are they pointing (a symbolic gesture) at what I think they’re pointing at? Are they color blind? Is this a psychological test? Are they gaslighting me? If none of these questions help, we might start doing multiple spot-checks on what kind of role the word 'blue', actually plays in our vocabularies. If the discrepancy is too jarring, and especially if we can’t explain it away, we may become very unsettled.

Pirandello, or rather, Moscardo, points out that representation also takes place inside us, not just in the outer world. In the outer world, the letters, c-a-t are not a cat and do not even look like a cat. Similarly, in the inner world, a bunch of neural stimulations in my brain are not a cat and do not resemble a cat. Furthermore, to compare inner worlds, the neural stimulation in your brain, may resemble those in mine (only because they are two samples of neural activity) but those that are your memory of a cat in your brain are more like the ones that are a memory of an elephant in your brain (because they are, after all, inside your brain) than they are like the ones in my brain that are my memory of a cat. So, how can we even make sense of the claim that you and I are both thinking of the same thing?

Moscardo’s words are symbols that encourage us to think about symbols. It can get downright upsetting. It may trouble me to realize that someone whom I thought loved me actually only loves the symbol she has created to represent me in her self-created world. And since anything can, in the right circumstances, represent anything else (let this biscuit represent a Russian tank) my lover may easily repurpose the symbol she created to represent me, so that it comes to represent someone else. At the end of Book Second, Moscardo becomes jealous not of another person but of Dida’s symbol for him, Gengé.

We humans have always gotten in trouble when we mistake a symbol for the thing it symbolizes. But creating symbols seems to be the thing we do best.

Our fly with an uneven nose sounds much like Buddha.