Good evening everyone, and welcome or welcome back to Pomus Aureus! Today we start our new literary journey with an introduction to novelist, essayist and playwright Luigi Pirandello, the author of One, No One and a Hundred Thousand. Don’t worry if Pirandello’s themes seem complex at first, I promise that his writing will be fun and much easier to digest than what my endless babbling makes it look like. Shall we begin?

Now it should be said that I have never been satisfied with portraying the figure of a man or a woman, however special or characteristic, for the mere pleasure of portrayal; or with narrating a particular episode, happy or sad, for the mere pleasure of narration; or with describing a landscape for the mere pleasure of description.

There are certain writers (and not a few) who do take such pleasure and, once satisfied, seek nothing more. These are writers more accurately defined as being of a historical nature.

But there are others who, beyond such pleasure, feel a more profound spiritual need, so that they cannot accept figures, episodes, or landscapes that are not imbued, so to say, with a distinct sense of life from which they acquire a universal significance. These are writers more accurately defined as philosophical.

I have the misfortune to belong with the latter.

From Pirandello’s preface to Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921)1

On the author

Luigi Pirandello was born in 1867 in the district of Caos (never a name was more apt) near the town of Girgenti, modern day Agrigento—for those keeping score at home, yes, this is our second Sicilian author in a row. Luigi’s father was a garibaldino, a veteran from the Redshirt army; his family owned a sulfur mine and was rather wealthy.

Young Pirandello was a voracious reader from childhood. Going against his father’s wishes, he pursued an education in the humanities and in 1887 moved to Rome to study philology; after a harsh dispute with a professor he fled to Bonn to finish his doctorate and eagerly took part in the cultural life of the city. Back in Rome, Luigi worked as a teacher, all the while publishing articles and short stories in the vein of literary realism. In 1894 he married Maria Antonietta Portulano, a shy girl chosen by his family; the couple had three children and got along surprisingly well despite their opposite personalities. That is, until the disaster of 1903.

A flood caved in the family sulfur mine, and just like that, the Pirandellos were ruined. Maria Antonietta, whose psychological state was already fragile, on reading the news underwent a profound shock. Her mental health never recovered, and she eventually died in a psychiatric hospital. Her husband and children were in turn deeply affected by her plight, and Pirandello’s views on life and art were fundamentally and permanently changed. He abandoned dry realism in favor of cognitive relativism, a literary philosophy imbued with humor and chaos.

His first major novel, The Late Mattia Pascal (1904), written at night as he watched over his wife, is a prime example of Pirandello’s themes: madness, change of perspective, escape from norms, search of identity. The deeply original novel was like a breath of fresh air in the stagnant European market and propelled Pirandello to fame. He went on to publish a prolific number of novels, short stories and essays, including On Humor (1908), fundamental to understand his philosophy and approach to art.

Life went on with its small and big tragedies. Pirandello’s son was wounded during WWI. His wife was interned. By the 1920s, Pirandello had discovered a new, major outlet for his genius: theatre. He dedicated himself to it with feverish enthusiasm and wrote more than forty plays, including Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921), his magnum opus. He founded his own theater company and toured Europe and America, reaching world fame. In 1934 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

In 1924, Luigi Pirandello joined the Fascist Party, receiving funds for his theater company in return. I will elaborate on his controversial connection to Fascism further down the article.

Pirandello caught pneumonia on set as he attended the filming of one of his novels. He died in 1936, leaving behind 42 plays, 7 novels, 15 short stories, 8 collections of poems, 13 between articles and essays. His work has been adapted so far into 38 films and 6 operas.

The lanternosophy of cognitive relativism

Do not panic! The words might sound complicated, but the concept is not too difficult to understand. Let’s break down the terms first, shall we?

Cognitive: Relating to or involving the processes of thinking and reasoning.2

Relativism: A theory that knowledge is relative to the limited nature of the mind and the conditions of knowing.3

Cognitive relativism essentially means that our ability to understand the world is limited to the small amount of information each of us can perceive and process. Still not clear? Pirandello comes to our aid with a fantastic metaphor from his novel The Late Mattia Pascal.

He expounded a highly specious philosophical concept of his which you might call lanternosophy. [...] this sense of life was like a little lantern that each of us carries with him, alight; a lantern that makes us see how lost we are on the face of the earth, and reveals good and evil to us. The lantern casts a broader or narrower circle of light around us, beyond which there is black shadow, the fearsome darkness which wouldn't exist if our lantern weren’t lighted.4

This is Pirandello’s “lanternosophy”: imagine, if you please, humanity roaming around in darkness, terrified by what it cannot see. Each of us is carrying a little lantern that we cast around, trying to make out what’s hiding in the shadows. It goes without saying that we cannot possibly understand—or even, you know, see—all there is out there in the world with the small light that we carry, which is our conscious being, our rational thinking. What’s more, what I can see with my lantern is going to be different from what you can see. Our truths will always be subjective and relative.

In every age, men usually come to some agreement on the opinions that give light and color to those big lanterns, our opinions on abstract terms like Truth, Virtue, Beauty, Honor, and what have you [...] The light of a common idea is fed by collective feeling; but if this feeling splits into factions, the lantern of the abstract terms still remains, of course, but the flame inside splutters and flickers and dies down, as in all the so-called transitional periods. And history is also full of fierce gusts of wind which suddenly blow out those big lamps altogether. How wonderful! In the sudden darkness, there is an indescribable scuffle of tiny individual lanterns; some go this way, some that, some try to move backwards, others in circles. Nobody can find the path; they bump into one another or cluster together in groups of ten or twenty, but they can't agree on anything, and they scatter again in great confusion, in fury and anguish, like ants who can't find the entrance to their anthill, trampled by the whims of some cruel child. 5

Not only we carry our little lanterns, we also build big lanterns and huddle together under their lights for comfort. These big lamps are abstract concepts like truth, honor, religion, patriotism, all theories that we like to call “true” and “absolute”. But are they really? Here we have people gathering under the lamp of Christianity, but what’s over there? Another crowd under the lamp of Islam; what we call truth and what they call truth are fundamentally different beasts. And then revolutions happen, public opinion sways, what is right and moral today becomes terrible and immoral tomorrow. How can we possibly decide what is truth and what is illusion, then?

Pirandello began his career as a realist writer, trying to describe the world in the most objective and deterministic terms possible. Then he lost all his money in a freak accident. His wife became insane. The absurdity of WWI happened. And Pirandello said, since life is chaos and uncertainty anyway, why are we so afraid to embrace the irrational? Here we all are, trapped in the limited light of our lanterns, lonely and too scared to take an explorative step into the darkness.

The struggle between life and form

Let’s follow Pirandello all the way down the rabbit hole. Let’s say we forget our lanterns and explore the darkness. What’s out there?

Life, Pirandello says, simply enough. All the magnificent and terrible chaos that is life. Eternally moving, eternally changing, like a swift river or lava burning everything in its path, life is our soul, our most intimate and most true self, our strongest instincts, passions and fantasies.

But just like magma solidifies into dumb rock, we force life, something so fundamentally fluid, into solid form. In our fear of the darkness, in our need to be neat and rational, we crystallize into unnatural forms that are only life-like. In other words, we wear masks.

Throughout existence a person will wear an infinite number of masks, some chosen, some imposed by society. Who were you when you woke up? And who did you become during the day? A parent? A colleague? A neighbor? A church goer? An activist? A thief? A lover? Did you act differently with each mask you wore? Did you tell something to your partner and the opposite to your employer? Did you buy groceries or clean your home and wished you were swimming in the ocean or eating your weight in chocolate instead? Did you say please and thank you to someone you wish you could punch in the face? Did you feel like an hypocrite?

Unfortunately, we are social animals. We need people to survive, but surviving around people is impossible, because existing next to someone cages and maims our very souls, Pirandello says. This is, in a nutshell, the great conflict between life and form, the paradox nature has concocted for us. We crave community but we will always be alone, no one will ever be able to see us for who we really are. My sense of self is different from what my friend thinks I am is different from what that guy down the street thinks I am. We change according to each person we meet, and we change within ourselves moment by moment, we are fluid beings oppressed by social conventions forcing us to be still.

Until it all becomes too much. One day you are a placid sheep grazing near the river, the next day that very river, the impetuous and perplexing flow of life, breaks its artificial banks and floods everything in its path. Pirandello’s characters often experience an epiphany, a random event making them realize that all is chance and illusion. They will struggle to break free, and they will not succeed.

Pirandello is not able to solve the paradox. His characters will never be able to reconcile life and form, their rebellions will inevitably conclude with depression, madness or death.

The bittersweet power of humor

I see an old lady whose hair is dyed and completely smeared with some kind of horrible ointment; she is all made-up in a clumsy and awkward fashion and is all dolled-up like a young girl. I begin to laugh. I perceive that she is the opposite of what a respectable old lady should be. Now I could stop here at this initial and superficial comic reaction: the comic consists precisely of this perception of the opposite. But if, at this point, reflection interferes in me to suggest that perhaps this old lady finds no pleasure in dressing up like an exotic parrot, and that perhaps she is distressed by it and does it only because she pitifully deceives herself into believing that, by making herself up like that and by concealing her wrinkles and gray hair, she may be able to hold the love of her much younger husband—if reflection comes to suggest all this, then I can no longer laugh at her as I did at first, exactly because the inner working of reflection has made me go beyond, or rather enter deeper into, the initial stage of awareness: from the beginning perception of the opposite, reflection has made me shift to a feeling of the opposite. And herein lies the precise difference between the comic and humor.6

Why did Luigi Pirandello, champion of hopeless cognitive relativism, choose to write comedies? His answer is right here: he doesn’t write comedies, he writes humor. He really wants you to understand the difference.

Comedy is superficial, it’s laughing at an old lady in a miniskirt. A comedian is an entertainer, not a philosopher. Pirandello calls the instinct of laughing at the absurd perception of the opposite: we perceive that something goes against accepted societal norms, and what’s our reaction? We mock it. Pirandello wants us to go deeper, his work aims to highlight the hypocrisy of society and to challenge it. The characters in his plays famously refuse to collaborate, break the fourth wall, interact with the audience. It’s funny on a surface level, troubling and discomforting when you consider the implications.

Let’s go back to the old lady in heavy makeup. Her inner desires (wanting to attract a younger man she is in love with) clash with societal expectations (presenting in an age appropriate way). It’s the paradox between life and form again, the woman is caught between the two and is deeply unhappy. Pirandello wants to shift our perspective, to embrace the tragedy within the comedy. The perception of the opposite becomes feeling of the opposite. In other words, he wants us to feel empathy and compassion. Is that the only way human beings can get a glimpse of each other’s souls? And will it ever be enough?

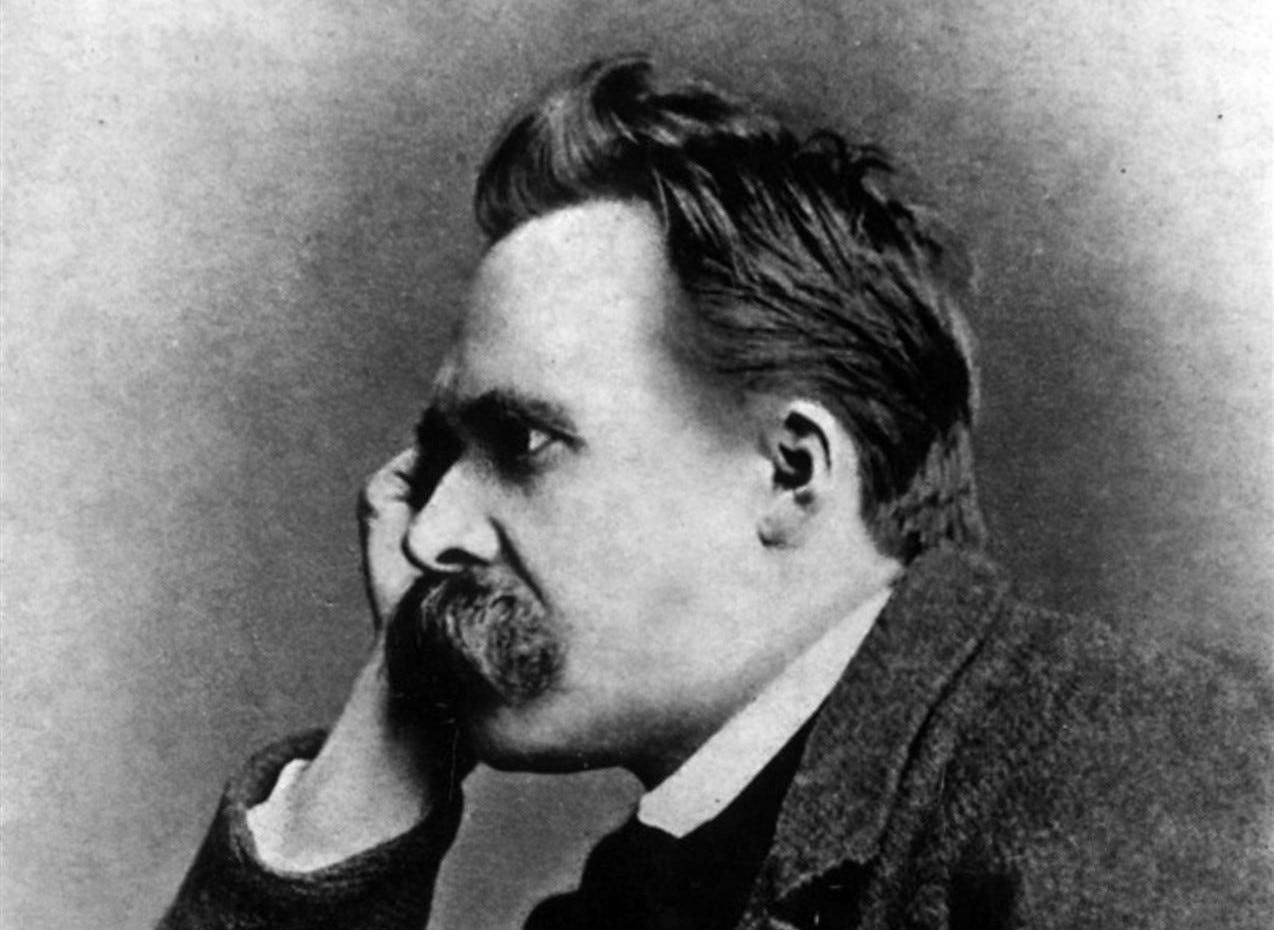

Pirandello, Nietzsche and Fascism

Nietzsche said that the Greek built white statues against the black abyss, in order to hide it. Those times are over. I shake them to reveal it.7

Once again, no need to panic! I won't go into the nitty gritty of Nietzsche's philosophy this late in the article. I'll just quickly point out that there are some obvious similarities between Nietzsche and Pirandello—relativism, the unnatural roles imposed by society, the exaltation of madness etc. Nietzsche was and still is the poster boy for fascist movements, and we can endlessly debate on just how much his philosophy was co-opted and exploited to fit the Nazi agenda. If anything, it's crucial to understand why his ideas were like catnip to Mussolini or the Nazi oligarchs.

Similarly, there is an obvious link between Pirandello's views and Fascism, and to be honest it has made me hesitant to cover his work—while I do wholeheartedly believe in the importance of studying and understanding our past, I also don't wish to cause unnecessary distress to any of my readers. Our current political climate is overwhelming, to put it mildly, and if you want to skip this author you have my blessing and sympathy. Look after yourself and your mental health as much as you can.

Like with Nietzsche, there is plenty of debate on just how much of a fascist Pirandello was. Some say his support was undeniable, others say that his work is the antithesis of fascist propaganda. An argument can be made for both opinions and for every nuance in-between, like Pirandello himself would say, truth is relative and each of us will understand it (and him) differently.

Here's my two cents, no more or less valid that anyone else's: Pirandello's ideas were born from the same fertile soil that breeds populism - economic uncertainty, weak and corrupt governments, shifting of moral values, disillusionment and unrest. When everything around you goes wrong it's only natural to look for radical and somewhat desperate solutions. Pirandello liked Mussolini's forceful takeover, his blatant dismissal of all rules and conventions.

Luigi Pirandello argued that the norms of society are artificial and human beings need to become more selfish, a very attractive line of thought to fascist movements. Crucially, he also advocated for empathy and compassion. As we read One, No One and a Hundred Thousand keep the two incompatible principles of selfishness and compassion in mind, I will be curious to see what kind of conclusions you'll reach.

Next week we will be reading and analyzing Book First, here you can find all the info you need. Don’t hesitate to ask if you need any help or clarification.

See you next Friday!

Three Plays by Luigi Pirandello, Oxford World’s Classics (2014), translated by Anthony Mortimer.

Cambridge dictionary definition.

Merriam-Webster definition.

The Late Mattia Pascal by Luigi Pirandello, New York Review Books (2005), translated by William Weaver.

See note above.

On Humor by Luigi Pirandello, University of North Carolina Press (1974), translated by Antonio Illiano and Daniel P. Testa.

Luigi Pirandello from a 1936 interview. Translation mine.

Thank you so much for the article—it was fascinating to delve into Pirandello's philosophy and his lanternosophy. Having read part of his book that we're discussing, I had a strong initial feeling that within "lanternosophy" there's a second word hidden besides "lantern"—"nose" (nos). While I'm not sure if this holds true in Italian, it works this way in English, Russian, and Polish versions. "Nose" sits in the middle, just as it does on the face. This will become the plot twist in our book. Your chosen Magritte illustration reinforces this idea perfectly—the huge nose transforming into a smoking pipe represents mask, perspective, and illusion all at once. If this nose found its way in unintentionally, that makes it even more brilliant within Pirandello's philosophy.

I'm ready to immerse myself in his paradoxes, in this unresolvable conflict—and illuminate my surroundings with my dim lamp.

Great introduction Ellie - thank you! I'm completely new to Pirandello. I've got a copy of the book but will probably lag dreadfully behind while I finish up with the To the Lighthouse readalong!