Welcome, everyone! Today we start reading One, No One and a Hundred Thousand by Italian Nobel laureate Luigi Pirandello; here is my introduction to the author, in case you missed it last week. The book is handily divided in eight sections that we’ll read in the span of eight weeks, you can find the schedule here.

Introduction

One, No One and One Hundred Thousand, the last and most poignant novel by Luigi Pirandello, was famously described by its author as “the complete synthesis of everything I did and the origin of what I will do.”1 Pirandello started writing it in 1909, but the gestation period was particularly long and fraught: only in December 1925 the first chapters began appearing on a literary magazine (and isn’t it nice that our book clubs let us recreate the long-lost experience of weekly installments?)

In typical Pirandello fashion the novel is short, easy to enjoy on a superficial level, packed with humor that, like the proverbial spoonful of sugar, helps the reader swallow and digest its complex themes. I won’t waste any more time on my introduction; just like Pirandello intended, we’re going to hold his hand and plunge head first into the troubled waters of his philosophy.

A note on the translation I chose: we are using the Samuel Putman’s 1933 public domain one since it’s the most readily available, you can find a cheap printed copy or you can download it in your preferred eBook format from the Internet Archive (let me know if you need any further help with these links or with locating a physical copy!) The more recent translation by William Weaver is excellent and if you already own it you are encouraged to go ahead and use it instead, but I find that Putman’s old-fashioned style is perfect for preserving and transmitting Pirandello’s deliberately archaic vocabulary.

Moscarda

In 1910 Pirandello told a friend that he was writing a book about a man called Monarda. The name was an invention by the author, a composite term he built using the Greek μόνος (mónos), meaning “alone, only, unique” plus the Italian derogatory suffix –arda. In the following fifteen years, Monarda the lonely evolved into Moscarda the fly. Let’s examine the name Pirandello chose more closely.

Vitangelo: From the Latin vitus, meaning “life”, and the Greek ἄγγελος (angelos), meaning “messenger”—used today to describe the religious and folklorist concept of Angels. Vitangelo is an old-fashioned name meaning “messenger of life”.

Moscarda: From the Latin musca, “fly” plus the derogatory suffix –arda. Moscarda is a humorous name that evokes to the mind a fat, annoying fly.

There’s only so much objective information we can learn about Moscarda. He is 28 years old, he lives in the fictional Sicilian town of Richieri, he doesn’t need a job thanks to his daddy’s money. If you squint you'll notice some autobiographical elements too: Pirandello also came from a rich family, he had an arranged marriage, he was fair among dark-haired Sicilians. Crucially, he was an abstract thinker in a materialistic world. Moscarda is quick to point out that his external circumstances are irrelevant and his whole being has always been dedicated to vague philosophizing.

But I may tell you that, in those days, I was prone to fall, at any word said to me, at the sight of a housefly buzzing about, into deeps of reflection and pondering that left me with a hollow feeling inside, and which rent my soul from top to bottom and tore it inside out like a molehill, without any of all this being visible on the outside.

Moscarda uses first person narration like an actor delivering a book-long monologue to his imaginary audience. Pirandello the playwright uses the language he learned on stage to bring us uncomfortably close to the narrator, it's one of the many magic tricks he has concocted to bypass all external influences and reveal the invisible inner life of a person. Vitangelo is indeed the messenger of life.

The nose

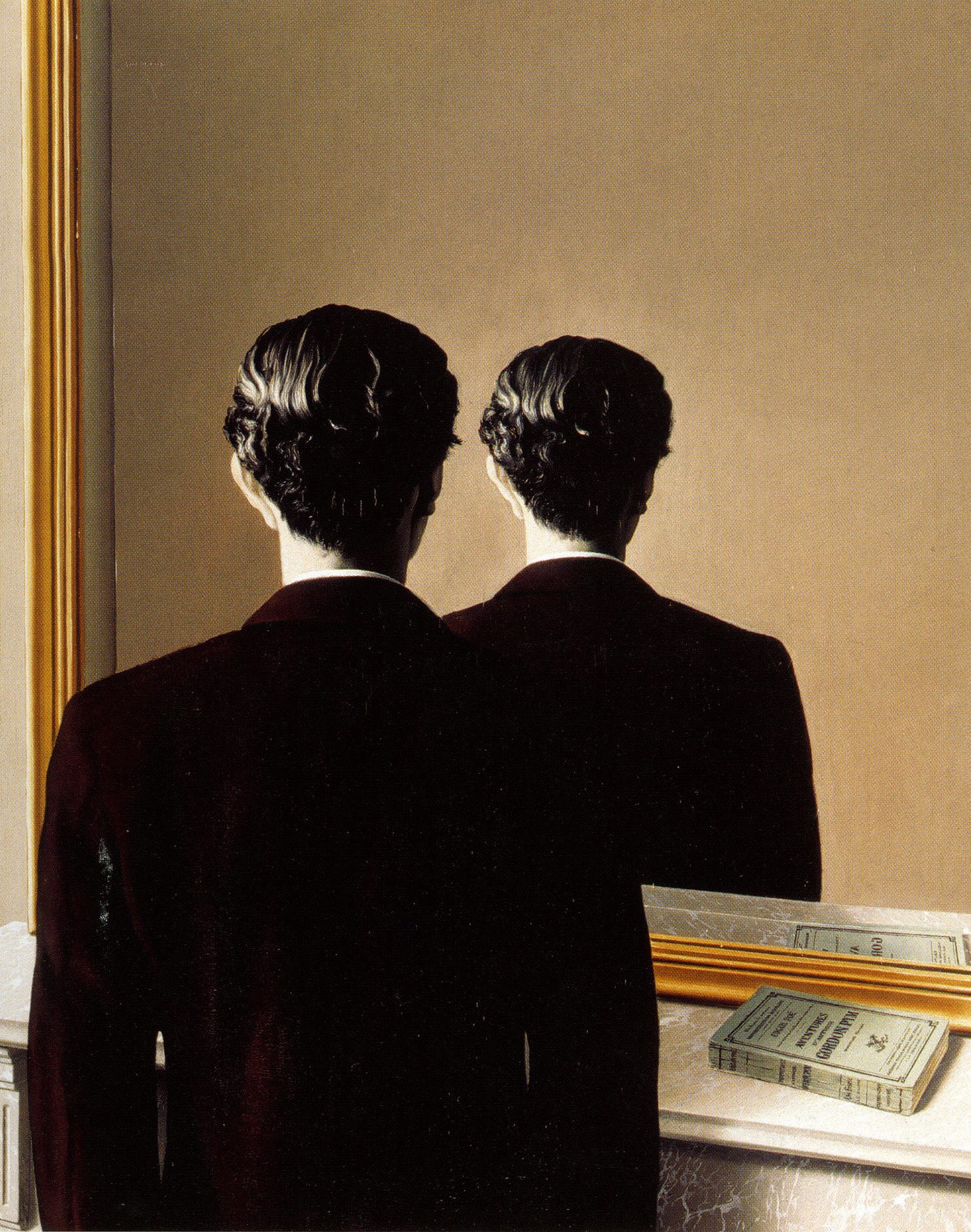

It's no coincidence that our book about inner life versus external appearances begins in front of a mirror. As Moscarda observes his nose, Dida his wife points out that it tilts a little to the side, a casual remark that will have unexpected and profound consequences. Moscarda is shocked to realize how uncomfortable this revelation has made him feel; chaotic being he is, he expresses his discomfort by pointing out minor physical defects in his acquaintances and causing a hilarious chain reaction of sly glances at mirrors all over town. We get our first example of the difference between genuine feeling and public behavior as the people of Richieri, obviously affected by Moscarda's revelations, pretend very hard to be above such frivolous thoughts.

Unlike others, Moscarda the annoying fly is eager to investigate why this new discovery feels quite so earth-shattering.

What relation is there between my ideas and my nose? For me, none whatever. I do not think with my nose, nor am I conscious of my nose when I think. But others? Others, who cannot see my ideas within me, but who see my nose without? For others, there is so intimate a relation between my ideas and my nose that if the former, let us say, were very serious while the latter was mirth-provoking by reason of its shape, they would burst out laughing.

Last week

noticed that noses are the perfect metaphor for Pirandello's philosophy of relativism. They are such an obvious, prominent feature in a person's face, yet their beauty is subjective and irrelevant in the grand scheme of things.Moscarda is hit like a train with the realization that his (not particularly) crooked nose is inevitably linked to the idea people have of him: when they think of Vitangelo Moscarda an image of his nose, red hair and short legs appear in their minds. But his actual being has nothing to do with those silly physical appearances! Meanwhile what's actually important, his rich inner life, is hidden away behind his face, invisible to the naked eye.

The reflection

Moscarda becomes obsessed with the idea of finding himself alone, not within his own thoughts, but outside, observing and listening to himself like a stranger would.

This was the way in which I wanted to be alone. Without myself. I mean to say, without that self which I already knew, or which I thought I knew. Alone with a certain stranger, from whom I darkly felt that I should be able never more to part, and who was myself: the stranger inseparable from me.

Today is easy to find candid photos or videos of ourselves, and most people have had the experience of feeling uncomfortable and awkward when they see their bodies out and about in the world. Back in the day, due the price of film and the bulky nature of cameras, most photography was unnaturally staged and candid pictures were rare. People's only chance to see a glimpse of themselves from the outside was to run into an unexpected mirror.

Moscarda, experimenting like a scientist, tries to recreate that very experience, and at first he feels like he's posing a puppet into various fake emotions. When he eventually replicates the optical illusion of meeting someone's gaze inside a mirror, he his engulfed in the depersonalizing, transcending, horrifying experience of staring at a stranger.

How could I endure this stranger within me? This stranger who was I myself to me? How go on not seeing him? Not knowing him? How remain condemned forever to bear him about with me, in me, in the sight of all others, and all the while outside my own?

While Moscarda contemplates his first, unsettling discovery, the body in the mirror sneezes. It’s a meat sack, an animal, it’s all urges and instincts, happy in its obliviousness, separated from the soul within and undeniably frail and mortal.

I was nothing. No one. A poor, mortified body, waiting for someone to take it.

Isn’t it enough to drive a certain kind of philosopher crazy?

I’ll stop here and leave you time to digest. During our time together we will delve deeper into the historical and personal reasons that brought Pirandello to form his unique life philosophy, but for now I’m curious to hear your first impressions.

See you next week for Book Second!

From a 1919 interview, translation mine.

Well that was a very interesting first chapter. I’ve never really thought before about the ‘me’ of my interior life versus the ‘me’ out there in the world. But they are indeed different people! I enjoyed the section where Moscardo is trying to ‘catch’ himself in the mirror. I remember doing this myself - though without all the philosophical thought - when I was about five. I’d try to move fast enough to see myself moving in the mirror. Unsurprisingly it never worked! I also thought it was interesting to be reading this in the age of social media when so many people are so invested in filming, documenting and seeing themselves ‘from the outside’. This section spoke to me:

“I could never meet, the one others saw living, but was invisible to me. I wanted to see and know him too, the way others saw and knew him.”

I wondered if this sense of knowing ourselves as others do is the motivation behind the compulsion to tik tok every moment for many people.

Thank you so much for the article! It's so interesting to read both the novel and your comments, and reflect on them.

In life, I'm also often accompanied by thoughts similar to those described by the novel's protagonist, but mainly I've pondered: "How can you prove that you are really you in this body, and not someone else?" And I haven't come to any conclusion, and now I have new thoughts because of Moscarda - how to get acquainted with your stranger-body. Is it really a stranger, just appearance, or can that other person have their own thoughts and emotions.

Here I think about the series Severance, where characters are divided into 2 separate personalities - one for work and one for the rest of life, and their thoughts/ideas never intersect. They have nothing in common except their body. I wonder if Moscarda also perceives that stranger as completely separate from himself.

And I have many questions about his wife! It feels like she's the reason for the protagonist's disorder. She's not presented here as a close person, as a "better half," "love" - but rather as someone who pushed him towards psychological problems, towards an existential crisis, and she doesn't let him "be alone." I wouldn't be surprised if his wife becomes his alter-ego, but one that represents the feminine manifestation in a man.

And I have questions: does the name Gengé have some special meaning, why did his wife call him that - will the protagonist explain this to us later?